The current coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19) has raised questions about herd

immunity, social distancing measures, and the relationship between these. In

particular, at time of writing the following Tweet has thousands of retweets

and likes.

I think that this presents an incomplete picture of the policy considerations.

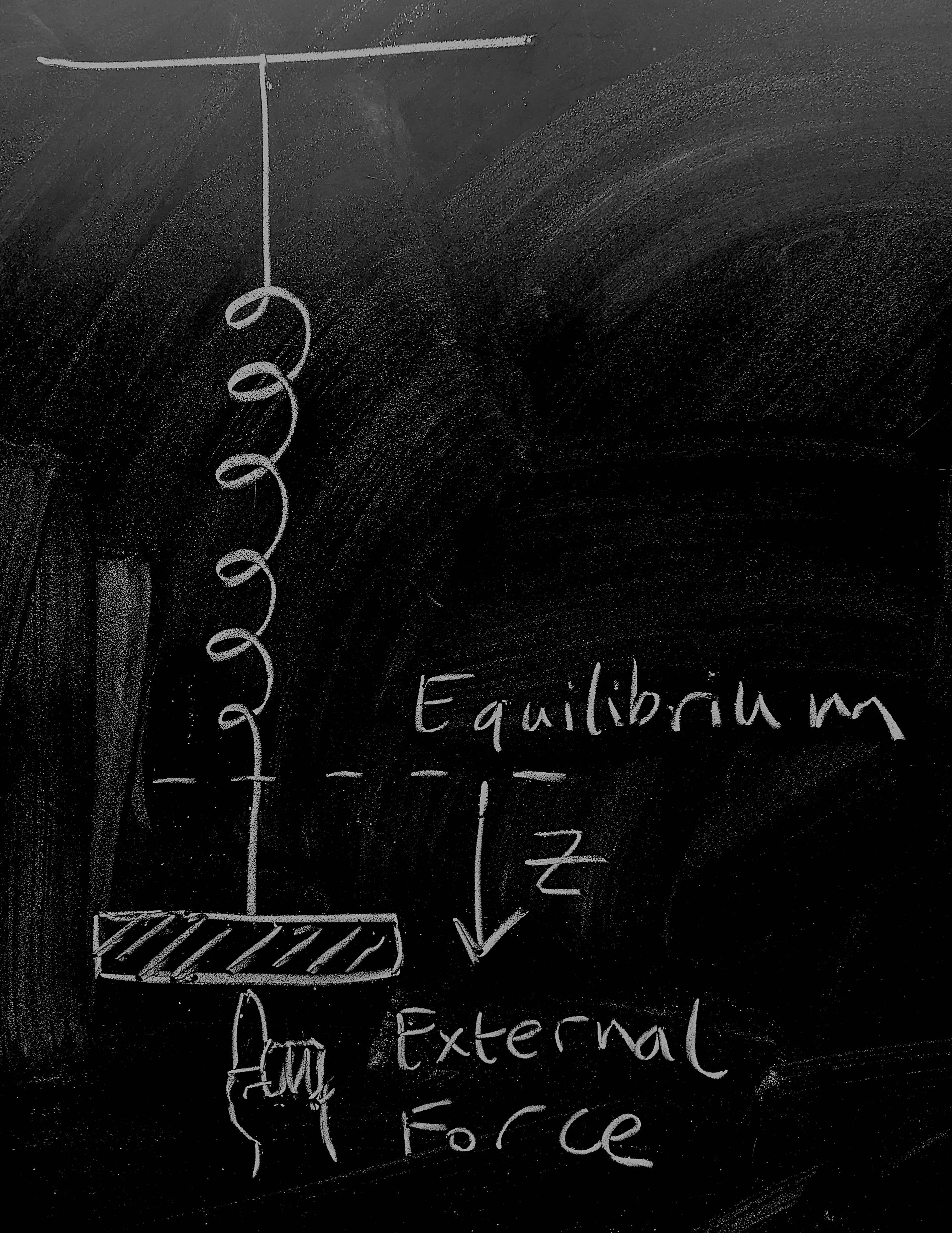

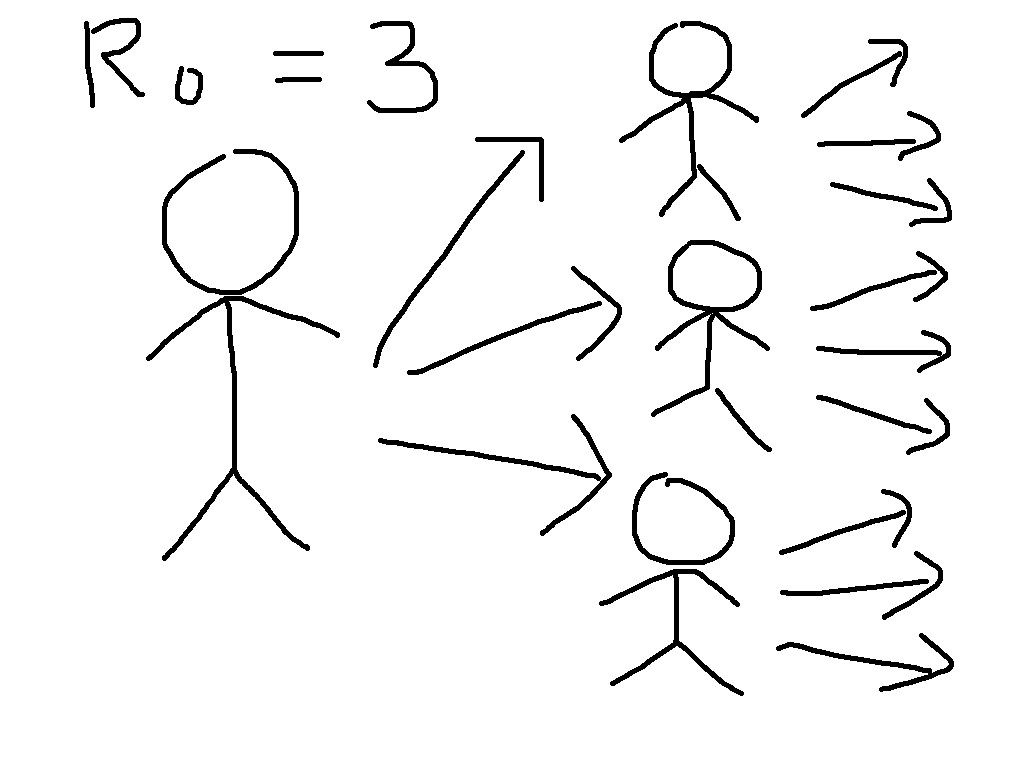

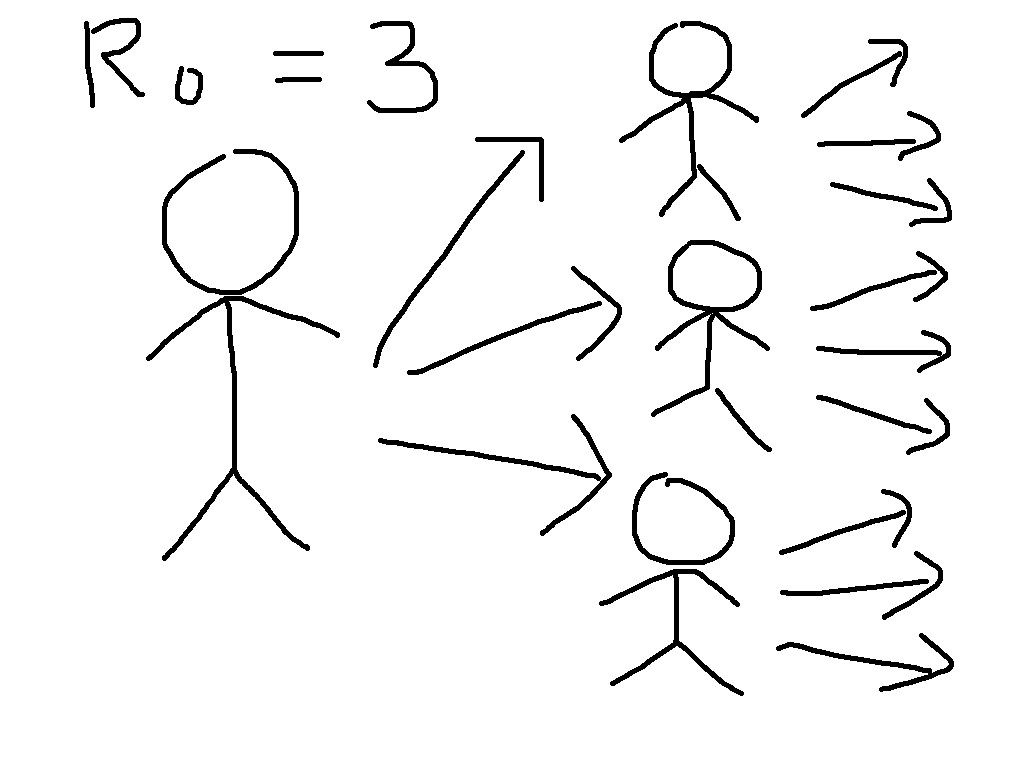

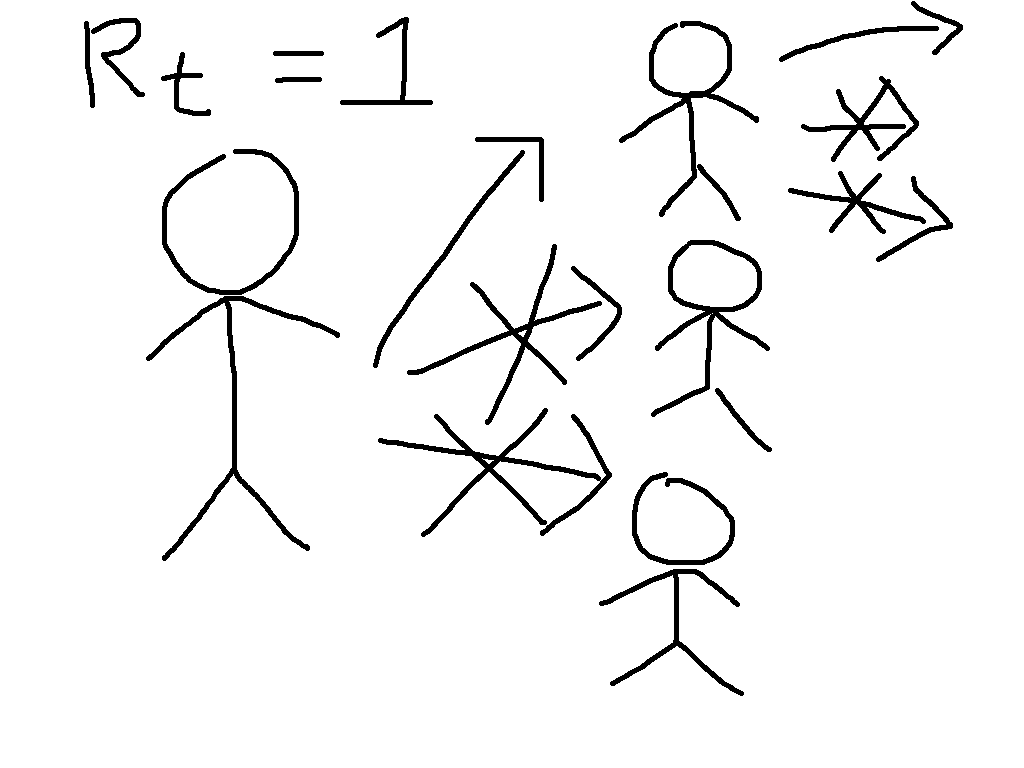

To see why, let us start by defining the most important concept in epidemic

modelling, the basic reproduction number \(R_0\). This is equal to

the average number of infections caused by a case early in the epidemic, so that

for \(R_0 = 3\), the early transmission tree might look something like

the cartoon on the left. This exhibits the exponential growth that is so worrying

at present. We have first one case, then three, then nine, then 27, then ...

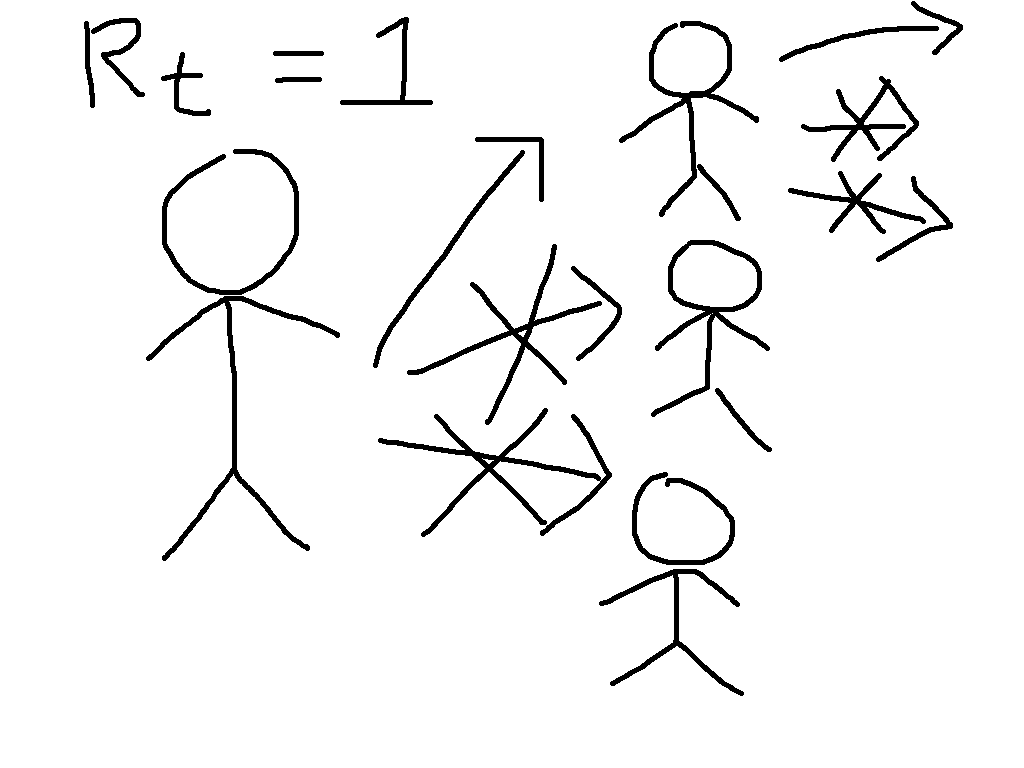

Now suppose that immunity has been built up, either through vaccination or by

illness followed by recovery, so that two thirds of people are immune. This

means that each case will have three contacts that would have caused infection

in the absence of immunity, but on average two of these will be immune and so

the situation looks more like the cartoon on the right. We say that the

reproduction number is reduced from its basic value to \(R_t = 1\).

While the individuals in the cartoon with a crossed out arrow pointing towards

them are literally immune, the people that they would have infected benefit

from herd immunity. They can be infected if exposed, but will not be. This

is particularly beneficial to the people who are particularly vulnerable to the

disease, who might die if they catch it. The general formula for herd immunity

is that when over \((1 - (1/R_0))\times 100\%\) of the population

is immune, then the epidemic will start to die out.

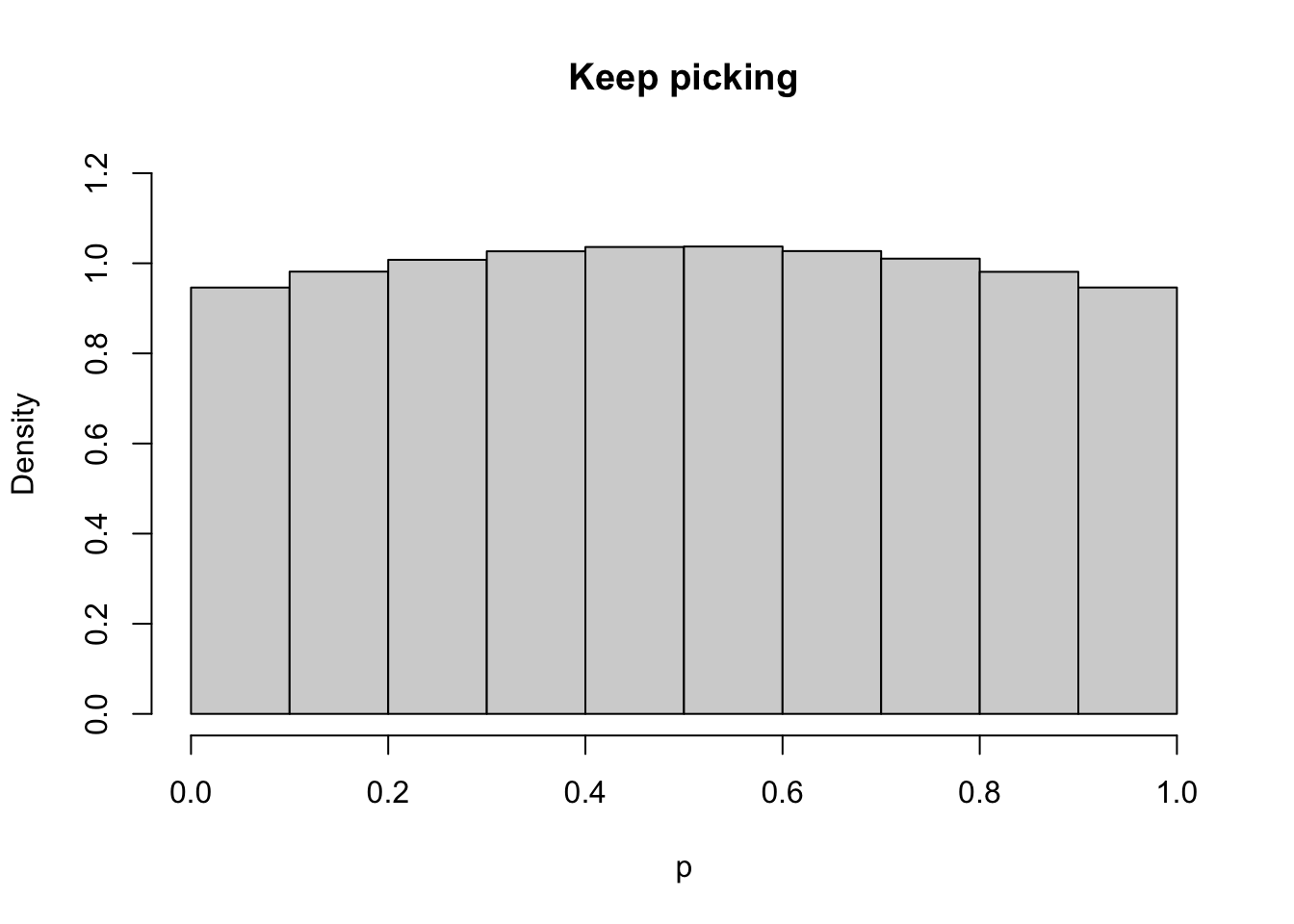

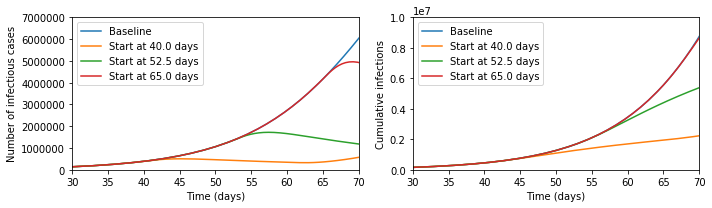

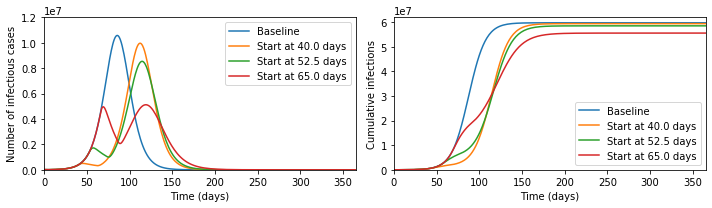

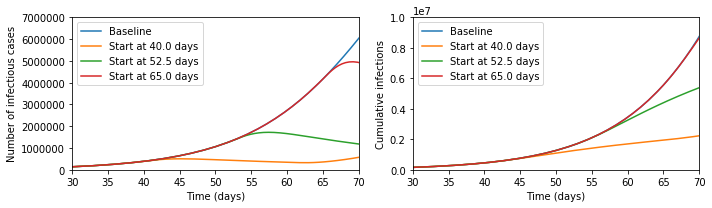

Now suppose we simulate a more realistic scenario. The Python code for this is

at the bottom of this post, and it is much simpler than the models that are

typically used to guide policy, but captures the basic phenomena of interest.

In particular, we suppose that we can reduce transmission through social

distancing measures like closing schools and workplaces, but that this is only

possible for three weeks. This represents the fact that the costs of not

educating children and not doing other activities can become quite large over

time, and in some cases can lead to levels death and illness that could exceed

those due to the unchecked epidemic. Running the epidemic model with these

interventions gives the following results for cases at a given moment and total

cases over time.

It seems that the Tweet was right - look at the difference the early intervention

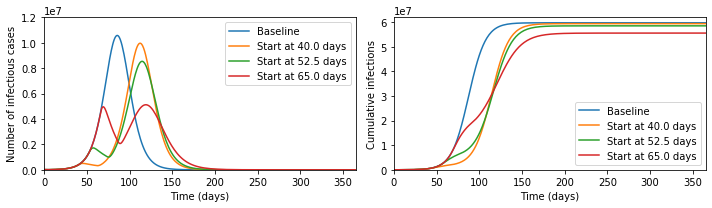

makes! But now let us zoom out of the graph; then the picture looks like the below.

In fact, the later intervention dramatically reduces the burden on the healthcare

system, cutting in half the maximum numbers ill and potentially needing treatment

at any one time, and significantly reduces the final number infected, which the

earlier interventions fail to do.

The reason that this happens is that social distancing measures do not lead to herd

immunity, so once they are lifted the epidemic starts again. In the absence of a

vaccine, it is therefore meaningless to speak about whether a policy 'aims' to get

herd immunity or not, since every country in the world will reach herd immunity

unless it is able to implement social distancing for an indefinite period of time.

What mitigation policies should aim to do, therefore, is to reach herd immunity

with the minimal human cost. This will be extremely difficult, and at every

stage we will be dealing with large uncertainties. I would not want to be the

person who ultimately made the policy decisions. But to say that early

interventions are always better is incorrect.

# Pull in libraries needed

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

from scipy import integrate

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Represent the basic dynamics

def odefun(t,x,beta0,betat,t0,t1,sigma,gamma):

dx = np.zeros(6)

if ((t>=t0) and (t<=t1)):

beta = betat

else:

beta = beta0

dx[0] = -beta*x[0]*(x[3] + x[4])

dx[1] = beta*x[0]*(x[3] + x[4]) - sigma*x[1]

dx[2] = sigma*x[1] - sigma*x[2]

dx[3] = sigma*x[2] - gamma*x[3]

dx[4] = gamma*x[3] - gamma*x[4]

dx[5] = gamma*x[4]

return dx

# Parameters of the model

N = 6.7e7 # Total population

i0 = 1e-4 # 0.5*Proportion of the population infected on day 0

tlast = 365.0 # Consider a year

latent_period = 5.0 # Days between being infected and becoming infectious

infectious_period = 7.0 # Days infectious

R0 = 2.5 # Basic reproduction number in the absence of interventions

Rt = 0.75 # Reproduction number in the presence of interventions

tend = 21.0 # Number of days of interventions

beta0 = R0 / infectious_period

betat = Rt / infectious_period

sigma = 2.0 / latent_period

gamma = 2.0 / infectious_period

t0ran = np.array([-100, 40, 52.5, 65])

def mylab(t):

if t>0:

return "Start at " + str(t) + " days"

else:

return "Baseline"

sol=[]

for tt in range(0,len(t0ran)):

sol.append(integrate.solve_ivp(lambda t,x: odefun(t,x,beta0,betat,t0ran[tt],t0ran[tt]+tend,sigma,gamma),

(0.0,tlast),

np.array([1.0-2.0*i0, 0.0, 0.0, i0, i0, 0.0]),

'RK45',

atol=1e-8,

rtol=1e-9))

plt.figure(figsize=(10,3))

plt.subplot(1,2,1)

for tt in range(0,len(t0ran)):

plt.plot(sol[tt].t,N*(sol[tt].y[3] + sol[tt].y[4]).T, label=mylab(t0ran[tt]))

plt.xlim([30,70])

plt.ylim([0,7e6])

plt.xlabel('Time (days)')

plt.ylabel('Number of infectious cases')

plt.legend()

plt.subplot(1,2,2)

for tt in range(0,len(t0ran)):

plt.plot(sol[tt].t,N*sol[tt].y[5].T, label=mylab(t0ran[tt]))

plt.xlabel('Time (days)')

plt.ylabel('Cumulative infections')

plt.legend()

plt.xlim([30,70])

plt.ylim([0,1e7])

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

plt.figure(figsize=(10,3))

plt.subplot(1,2,1)

for tt in range(0,len(t0ran)):

plt.plot(sol[tt].t,N*(sol[tt].y[3] + sol[tt].y[4]).T, label=mylab(t0ran[tt]))

plt.xlim([0,tlast])

plt.ylim([0,1.2e7])

plt.xlabel('Time (days)')

plt.ylabel('Number of infectious cases')

plt.legend()

plt.subplot(1,2,2)

for tt in range(0,len(t0ran)):

plt.plot(sol[tt].t,N*sol[tt].y[5].T, label=mylab(t0ran[tt]))

plt.xlabel('Time (days)')

plt.ylabel('Cumulative infections')

plt.legend()

plt.xlim([0,tlast])

plt.ylim([0,6.2e7])

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()