Caffeine in Pregnancy, Weak Identifiability, and Working with the Media

A recent Paper in BMJ Open deals with the question of maternal caffeine intake and childhood obesity.

I worked with the Science Media Centre to produce a Press Release in which I made the comment:

"This study makes the headline claim that in a population of over 50,000 mother-child pairs, caffeine intake is positively associated with risk of childhood obesity. Let us make a ‘back of the envelope’ calculation on one of the outcome measures using the cup of instant coffee per day as a measure of the mother’s caffeine intake.

If we take 100 children whose mother group had the lowest caffeine intake (1 cup or less) then at age three, around 11 will be obese; in the next group (1-4 cups) there will be one additional obese child (12 in total); in the next (4-6 cups) there will be an additional two (14 in total) and in the group with highest caffeine intake (6 or more cups) there will be an additional three (17 in total).

The main problem with the study is that maternal caffeine intake is strongly correlated with other relevant factors, and so these should be controlled for. In the authors’ statistical analyses, the ‘best fit’ models they’ve used suggest around half of the additional cases of obesity in children of age 3 are explained by caffeine rather than, say, calorie intake of mothers. But since the caffeine and calorie intake are correlated, the existence of a ‘best fit’ model with equal weighting on both means we actually can’t say whether a model looking at just calorie intake of mothers would be an equally good explanation of child obesity. It also says nothing about whether including a new explanatory measure, such as the child’s calorie intake, would change the model.

As such, the evidence provided in the study for a causal effect is extremely weak and the statement from the authors that 'complete avoidance might actually be advisable' seems unjustified, particularly when we consider the effects that such a restriction might have on wellbeing of mothers."

This story was quite widely covered, but most papers took the same approach as iNews and only quoted my main conclusion, but not the reasoning.

So let's consider a simple exaple that exhibits the main problem, in particular the following contingency table. This is much smaller than the original study, but the same phenomenon is exhibited by larger populations with more explanatory factors:

Caffeine Intake |

|||||

Low |

High |

||||

Calorie Intake |

Low |

Healthy |

Overweight |

Healthy |

Overweight |

63 |

7 |

3 |

2 |

||

High |

Healthy |

Overweight |

Healthy |

Overweight |

|

2 |

3 |

5 |

15 |

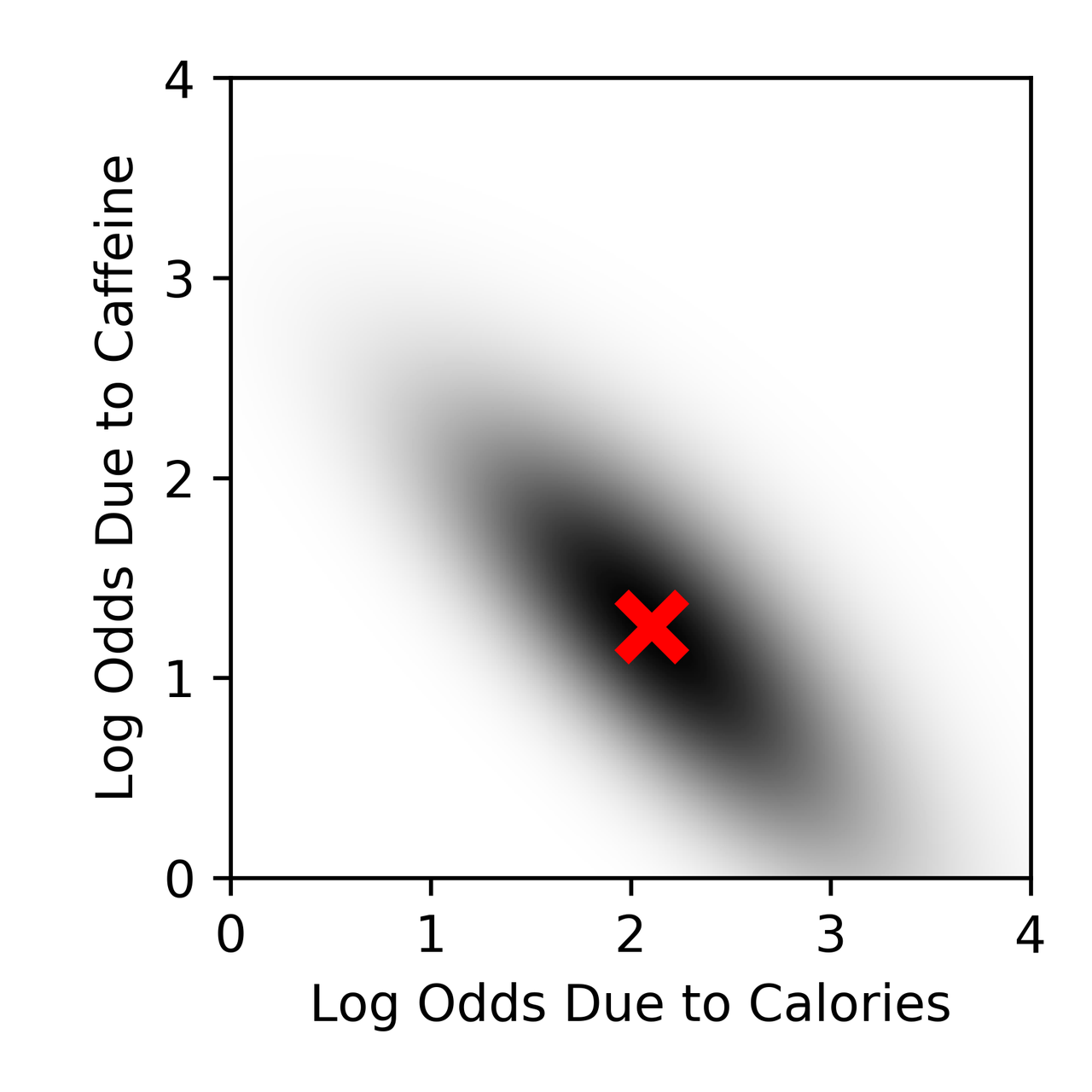

||

Note that 68% of the high caffeine group is overweight, while only 13% of the low caffeine group is, but we note that calorie intake may be an issue so let us perform logistic regression as the authors did, letting \[\mathrm{Pr}(\mathrm{Overweight}) = 1/(1+ \mathrm{exp}(-\beta_0 - \beta_1 \times \mathrm{HighCalorie} - \beta_2 \times \mathrm{HighCaffeine})) \mathrm{ ,}\] where \(\beta_0\) is the intercept, \(\beta_1\) is the log odds due to calories and \(\beta_2\) is the log odds due to caffeine. Setting the intercept at its maximum likelihood value, the maximum likelihood values for the other parameters are shown as the cross below, which attributes roughly equal importance to the two factors:

Behind this cross is a shaded region with intensity equal to the likelihood of different parameter combinations - and we note that there is still a reasonable amount of shading in the area where \(\beta_2 \approx 0\). This is a special case of a general phenomenon called weak identifiability, and it is something I've done a bit of work on - there are various ways to deal with this, but its presence is the reason that evidence for a causal effect is weak in the original study.