Brachiopods

Meet a member of the phylum Brachiopoda:

Brachiopod Peregrinella peregrina, Late Cretaceous, France. ~8 cm long.

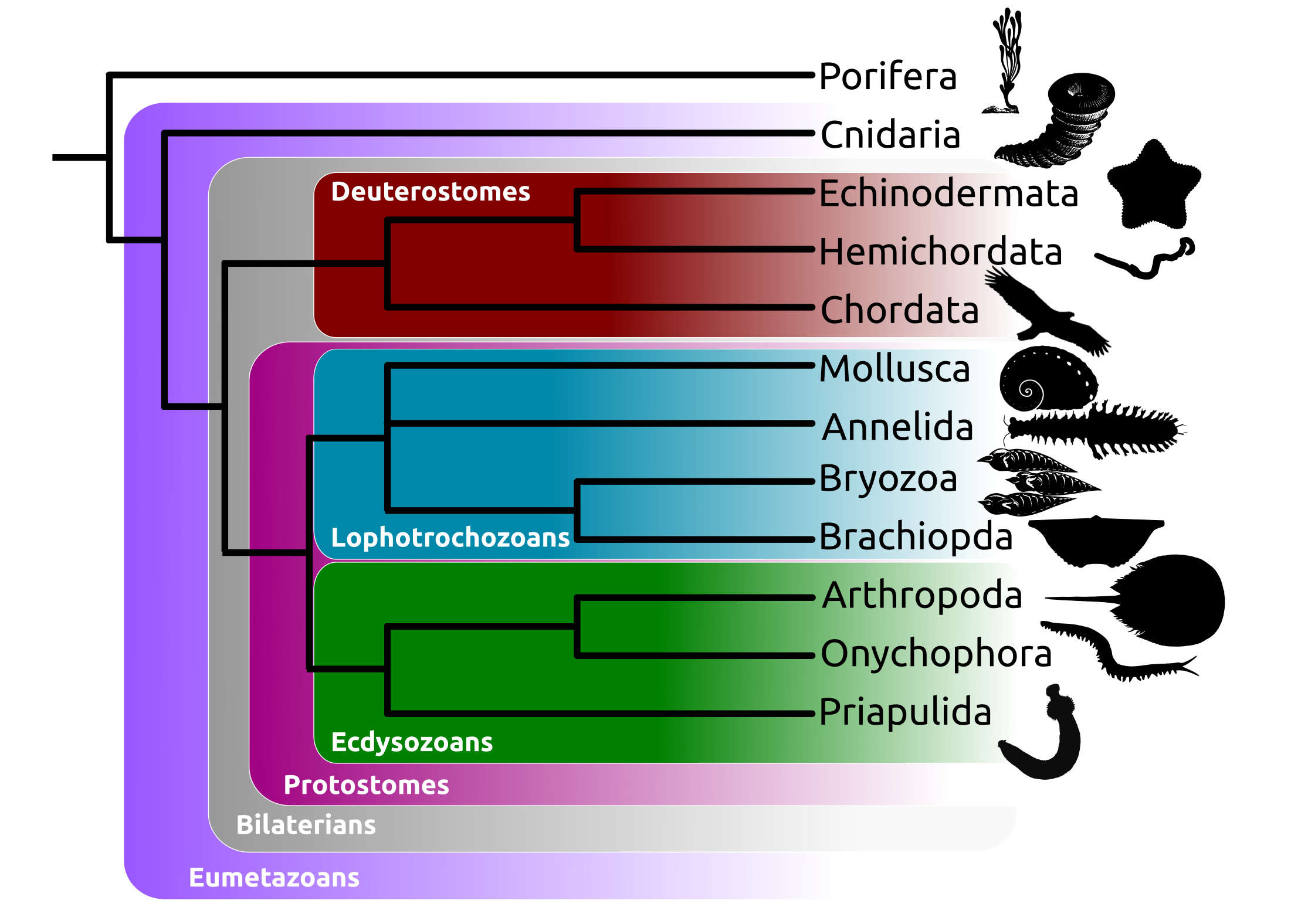

These animals originate in the Cambrian, were hugely successful filter feeders in the oceans of the Palaeozoic Era, and still exist, but are nowhere near as successful today. On our tree of life, we can find these in the clade Lophotrochozoa – a group united by developmental biology, and a feeding structure called the lophophore.

Bryozoa

Next up we have the Bryozoa, another phylum of lophotrochozoans, closely related to the brachiopods!

A fossil bryozoan (Polypora elliptica), from the Carboniferous Thrifty Formation of Eastland County, Texas. Max ~4.5cm.

The fossils of these creatures look like nets - they are actually a number of animals living in a colony, and filter feeding. They appeared in the fossil record in the early Ordovician, and are still around today.

Echinoderms

Echinoderms are the only animal group to have pentaradial (five-way) symmetry. They are the sister group to the hemichordates, and in turn, to the chordates on our tree of life - in the deuterostome clade. Here is a fine example:

Blastoid Pentremites robustus, Lower Carboniferous, found in Indiana. Specimen ~4.5 cm long.

The Echinodermata includes the stalked crinoids/sea lillies, sea urchins, starfish, and brittle stars. Their fossil record is super duper interesting as there is quite a lot of extinct diversity (they have been around from the Cambrian, and are alive today, but only five lineages, out of many more, survive), and they went through a phase in the Cambrian where some had no symmetry at all! The above is a member of an extinct group called the Blastoids.

Ostracods

Ostracods are small crustacean arthropods (so in the clade ecdysozoa). Here is a rock chock full of them (they look a bit like kidney beans as they have a bivalved carapace around their body):

A ~15 cm Ordovician limestone packed full of fossil debris, including ostracods fromLafayette County, Wisconsin.

The ostracods appear towards the end of the Ordovician, and they are pretty much ubiquitous as small fossils from that point onwards. They are used to date rocks, and to understand the environments they were deposited in. They are unique in having individual sperm which, once uncoiled, are actually longer than their entire body.

Trilobites

Trilobites are the only major arthropod group to have gone extinct. Boo. They were around from the Cambrian to the end of the Permian, and during this time – especially earlier in this range, they were the most speciose animals, as far as we can tell from the fossil record.

Specimens of Homotelus bromidensis an Ordovician trilobite. These were found in the Bromide Formation of Carter County, Oklahoma. They are housed by the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (specimen number PRI 45505). Longest dimension of this piece of rock is ~14 cm.

They're gorgeous, aren't they?

Ammonoid

Ammonoids were really successful cephalopods (the group that also includes squid, octopodes, and cuttlefish). They are thus molluscs (and lophotrochozoans too!). Unlike the other groups I mentioned, these molluscs had external shells, which are often preserved in the fossil record:

This is an ammonite cephalopod - Cleoniceras besairiei. It is Cretaceous in age. Maximum diameter ~12 cm.

They were around from the Devonian to the end Cretaceous, and were free swimming creatures. They are really useful for dating rocks… and studying evolution.

Eurypterids

Otherwise known as sea scorpions, these were aquatic chelicerates (i.e. a member of the arthropod group that includes the arachnids and horseshoe crabs [which are not, usefully, true crabs]). Aren't they cool?

A Slurian sea scorpion (Eurypterus remipes) from Herkimer County, New York. Fossil ~12.5 cm in length.

These creatures were around from the Ordovician to the end Permian, and were predators in the Palaeozoic oceans, especially those of the Silurian.

Corals

There are two groups of extinct corals, that were around during the Palaezoic – Rugosa and Tabulata. Corals alive today are a member of a group (Scleractinia) that appeared during the Triassic. Corals are cnidarians in our tree – so metazoans, but not quite bilaterally symmetrical ones. They lack, for example, a through-gut. Here are the extinct groups:

Rugose corals

Here is an example of the order Rugosa, around from the Ordovician to the end Permian. Bear in mind this group can be either solitary (as you see here) or form colonies.

A fossil rugose coral (Heliophyllum halli). This is Middle Devonian in age, sourced from the Moscow Formation of Erie County, New York. Specimen ~11cm long.

Tabulate corals

This is a member of the other major fossil order - the Tabulata. This group was also around from the Ordovician to the end Permian. Tabulate coral were only colonial.

A tabulate coral (Emmonsia emmonsii) – also Devonian in age, but from the Onondaga Limestone of Genesee County, New York. Longest dimension of specimen ~8.5 cm.

Bivalves

More molluscs! These ones are the bivalves - think muscles, clams and oysters:

This is a fossil bivalve – Mercenaria mercenaria. It is quaternary in age, and was found in St. Mary’s County, Maryland. Specimen ~10 cm wide.

Bivalves have, uh, two valves, with a body inbetween. They appear in the early Cambrian, and are around today: they became prominent filter feeders in the Mesozoic oceans. They are common as fossils.

Gastropods

A final mollusc group for your delectation. Slugs and snails are gastropods, and there are a lot of marine members of this group that have spiral shells with good preservation potential – so are common in the fossil record.

This is a fossil gastropod called Naticarius plicatella. Note that inside its apeture, you can see a thing called the operculum (trap door) which is not normally preserved. This particular critter is Pliocene in age (it's from the Pinecrest Beds of Sarasota County, Florida, FYI). Specimen ~3.5 cm long.

Conodonts

3D models for these microfossils are hard to come by, I'm afraid, sorry. They represent the feeding apparatus of an extinct vertebrate group. They were around from the Cambrian to the end Triassic. If you want to learn more about them, this is a good source. These are somewhere around the chordates in our tree.

Dinosaurs

Given that I couldn't find a 3D model of the above, here is a 3D model of a dinosaur. These creatures did pretty well for along time, surviving from the Triassic until today. Well, the non-avian (i.e. non-bird) dinosaurs died out, but the clade as a whole is still very much with us.

This is actually a model of a cast of a Tyrannosaurus rex skull. But is still cool.

Dinosaurs aren't massively common as fossils compared to, say, marine invertebrates, but many people spend time studying them, their evolution, and their ecology. Tyrannosaurus rex is a large theropod - a member of the group that gave rise to birds. If you want to learn more about dinoarus, EES currently offers a third year dinosaur palaeobiology module. In case you didn't guess it, these are chordates.