Introduction and biology

The molluscs have deep roots — they have Precambrian origins, had a diversity of weird forms in the Cambrian, and there are a number of groups that have survived from early in the Palaeozoic through to today. Other groups were very successful, but have now gone extinct. So we'll start here with a quick overview of the biology of the group, their evolutionary history, and when their diversity through geological time.

Summary

Key points to take away from this video are:

- Molluscs form a diverse group of Lophotrochozoa that includes slugs, snails, squid, cuttlefish, octopuses, ammonoids and all manner of marine shellfish such as clams, mussels, and oysters.

- Their body plan has four features:

- A head with sensory organs and a feeding structure called the radula.

- A foot that is used for locomotion.

- A dorsal mantle that secretes the shell.

- A colemic cavity with organs in, and a mantle cavity with gills.

- The group has its origins in the Precambrian, and has diversified from an array of sometimes weird-looking Cambrian animals.

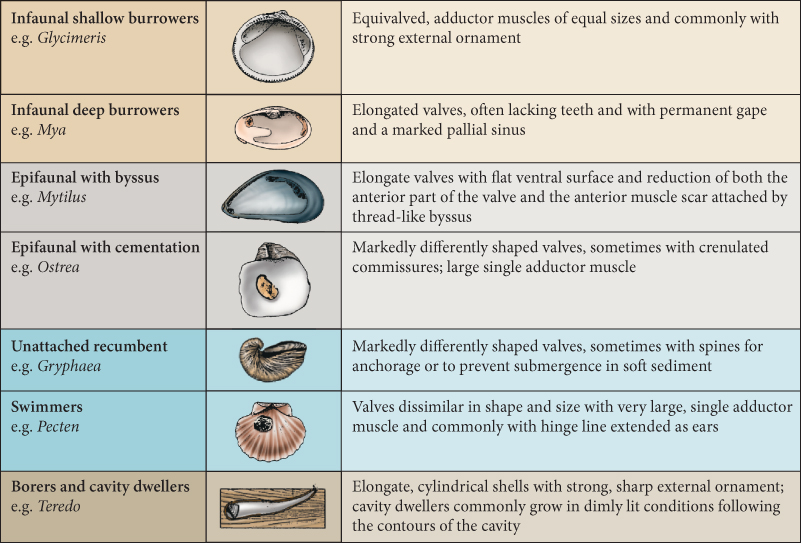

- The ammonoids, gastropods, and bivalves are all important fossil groups.