Content:

Overview-

Breakdown of set task

Question1) Explain how increasing international trade has come about

- It is the intention of this presentation to show how international trade has accelerated in modern economics.

Question 2) How is this argued to have affected wage inequality in developed countries

- The presentation aims to cover how wage inequality has been affected in developed countries, whether positively or negatively.

Question 3) Is there any empirical evidence which either supports or refutes the idea that trade is responsible for the big changes in inequality that we observe?

- The presentation aims to provide clear facts and figures therefore providing evidence to support conclusions.

Facts about wage inequality:

Adrian Wood in 'How Trade Hurt Unskilled Workers' highlights some key facts about the situation of wage inequality.(18)

- The supply of skilled labour in developed countries has slowed over the past decade.

- The demand for unskilled workers has decreased over the past decade relative to the demand for skilled labour in developed countries. The shift in demand has increased wage inequality. In situations where institutions prop up unskilled workers' wages, the unemployment amongst the unskilled has increased.

- Employment in the manufacturing industry has declined in developed countries.

- Changes in the labour markets coincided with 'rapid diffusion' (p58) of computers in the workplace.

- Trade has made some contribution to wage inequality, although how much contribution is disputed.

- Found that tariff barriers on manufactured goods entering developed countries declined from an average of 40% in the late 1940s to 7% by late 1970s.

History of Trade theory:

Increase in International trade:

International trade has taken a more significant role in modern economic thought due to its political, social and economic development. The term 'Globalization' was famously coined by the Harvard business school professor Theodore Levitt, since that time it has become a modern by word in explaining increases in international trade. Globalization gives birth to the concept of thinking of a domestic economy in an international perspective. The significance of globalization is that it deals in factors that have a direct implication on wage inequality, including Trade, Technology, Immigration (especially in relation to skilled and unskilled labour) and capital flows. International trade has grown in significance not simply on an economic level but also on a social and political level as well. This has occurred, in part, due to the by products of globalization which include changes in communication, transportation and computer technology. (17)

The benefits of offshoring and outsourcing are too great for a company to be able to protect workers in a developed country. If some people can use their skills more cheaply than others, companies will make the most of this to be cost effective. Workers in developing countries have a comparative advantage. This global market which has emerged has helped to bring international trade to the forefront of economic theory as more countries are realizing the benefits of investing in and trading with another country rather than being a manufacturing autarky.

| Name | Picture | Country | Background | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| David Ricardo (19 April 1772 - 11 September 1823) |

|

Great Britain | Most significant contribution to economics is his work on Comparative Advantage. | ||

| Adam Smith (16 June 1723 - 17 July 1790 ) |

|

Great Britain (Scottish) | Seen as forefather of modern economic theory, author of The Wealth Of Nations, arguably the first works on economic theory. | ||

| Heckscher-Ohlin Bertil Ohlin, (23 April 1899- August 1979) Eli Heckscher, ( 24 November 1879 - 23 December 1952) |

|

Swedish | Developed simple dichotomous model of international trade, with two countries, two goods and two factors: Factor proportion hypothesis. | |

|

| Stolper-Samuelson Wolfgang Stopler,13 May 1912- 31 March 2002 Paul Samuelson, May 15, 1915 (Age 95) |

|

Austrian & US |

Postulates the relation between relative prices of output goods and relative factor rewards, specifically real wages and real returns to capital. |

||

| Paul-Krugman Born 28th February 1953 |

|

US | Famous for his elusive link betweeen trade and wage inequality; sometimes referred to as Krugman's Conundrum |

History

International trade is seen as the engine of growth and development, whose potential for growth is driven by the comparative advantage paradigm. According to this principle, a country will specialise in the production of a good in which it has a lower opportunity cost then another country, with these goods then freely traded among one another, will prove mutually beneficial for both countries. It is from the insight of the economist David Ricardo (1817) that the backbone of modern trade theory was established. His work followed from that of Adam Smith (1776), Ricardo isolated the importance of comparative rather than absolute advantage in trade in order to maintain a higher collective profitability from trade.Ricardo's work focused on the way in which comparative advantage was obtained, either through technological advancement or by superior means of production. The comparative advantage model of trade has been critcised due to the number of assumptions that the model is based upon. The work of David Ricardo is often used in support of free trade policy.

International trade theory was taken on and developed by Heckscher-Ohlin and their work on 'Factor proportion Hypothesis'. The work of Heckscher-Ohlin showed how the opening of trade offers new areas to specialise productively as well as raising the overall average level of productivity of domestic industries. One of the limits of this theory is that it fails to explain patterns in modern manufacturing activities between industrialised economies. This theory was developed by Stolper-Samuelson and their work, which dealt in the price of output and the returns on factor input.

Sach and Shatz in 'Globalization and the US Labour Market' discuss how international trade has come about for the U.S; a good example for a developed country case study (15). The article states how the US abandoned their protectionist trade by opening up into the free market economy. They started to directly invest in developing countries therefore consolidating a business link, namely China in the early 1980s and Latin America in the mid 1980s. They greatly increased their exports to developing countries especially East Asia as a result of the high rate of investment in these countries. Decreased transport and communication costs have encouraged trade and multinational investment.

Brief history of wage inequality:-

While wage inequality and trade have always been a deep seeded issue in economic discussion it is the aim of this discussion to show whether it is the largest issue. Due to the rise in unemployment and wage inequality in OECD countries during the 1980's the role of international trade has come to the forefront of economic discussion as to whether it is the cause of this trend. An OECD study showed how inequality increased in 12 of 17 member countries during the 1980s, compared to the1970s where inequality generally decreased or remained stable (OECD, 1993b)(1). The Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson (HOS) trade model provides two predictions concerning the links between trade and wages. This theory predicts the equalisation of relative factor prices, such as labour. This suggests that the price of domestic unskilled labour will fall due to the opening of low wage countries with a relatively higher unskilled labour force. The other effect is the 'Stolper-Samuelson' effect in which the there is an absolute fall in real wages of unskilled workers due to competition from countries with a relative abundance of unskilled labour (12). While these two theories sound similar the difference is that in one, the opening of trade allows foreign competition to effect simply the domestic unskilled labour market. The other theory is that with unskilled labour being freely traded between countries of high concentration and low concentration, it will lower the absolute level of unskilled wages. However these models are working on the assumption that it is a perfectly competitive market which is not the case in real studies. This is why other theories were developed such as that by Lawrence and Slaughter (1993) who argued that unskilled labour-saving technological progress, such as the use of computers, was a more plausible argument for the relative wages shift in the 1980s (1). While trade theory goes some way in explaining wage inequality not all its factors explain areas such as the wage differentials increasing among workers within the same demographic and skill groups. The wages of workers with the same education, age, sex, occupation and industry were much more dispersed in the 80's compared to the 70's.

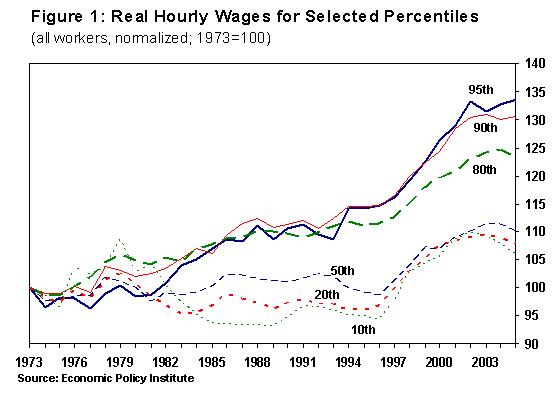

As you can see from Figure 1, wage inequality is widening dramatically, year on year. In all percentiles, the real wages appear to be increasing the wage gap between those in the upper percentiles and those in the lower percentiles is rising dramatically. When we look at the base year of 1973, we see very little discrepency in wages between percentiles, with only around 10% discrepency between percentiles. This is a very different picture when we look at 2003, we see that wage discrepency and thus inequality has increased nearly four-fold to nearly a 40% difference between the highest and lowest percentiles.

Reference^(^24)

How To Measure Wage Inequality

See: measurements of wage inequality

The Gini coefficient is a simple, single number, summary statistic describing the extent of inequality. It is often used in official publications as a statistic to summarise the distribution of income or wealth. Here it is used to characterise inequality of the distribution of labour market earnings. It ranges from 0 (complete equality) to 1 (complete inequality).

Machins studies are centred around the Gini Coefficient. The gini coefficient is a good statistic for describing aggregate inequality trends, but it is less useful for identifying shifts that lie behind the overall change. A percentile is a value on a scale of 0 to 100 that represents the percent of the distribution that is equal to and below the value. For example, a variable at the 80th percentile is equal to or higher than 80% of the components of the distribution.(9) (23)

International Trade as an Explanation of Wage Inequality:

The expansion of trade between developing and developed countries is argued to be a main cause of the deteriorating situation for unskilled workers in developed countries. So, the increase in the relative demand for skilled workers can largely be attributed to the growth of international trade. Take the U.S for example, in 1970 their ratio of exports and imports to GDP stood at 8%; but in 1996, this ratio had risen to 19%. This increase is due to the increase in trade with less-developed countries, who accounted for 40% of imports in the same period.

Countries tend to export different types of goods than it imports. According to Borjas, the workers employed in the importing industries tend to be poorly educated, whilst those employed in the exporting industries tend to be well educated (4 & 5). So because foreign consumers have increased their demand for skilled goods and services over previous decades, the demand for skilled workers has increased. Similarly, as developed countries import low skilled goods, often to save on cost, the demand for low-skilled labour has decreased. Developing countries are labour intensive, developed countries are skill intensive. Thus in developed countries, with rising exports and even higher rates of imports there is a large demand for skilled labour and an ever decreasing demand for unskilled labour.

Thus the graph below represents the outwards shift in the relative labour demand curve. The perfectly inelastic supply curve moves to the right from S to S1 as the relative number of skilled workers increases. As the rise in the relative wage from R to R1 is then explained from the shift in demand for skilled workers from D to D1. Thus the labour market moves from point A to point C.

Reference^(^32)

X Axis - Relative Employment of skilled workers.

Y Axis - Relative Wage of skilled workers.

The industries that have been hardest hit in developed countries by increased imports are manufacturing industries, such as the automobile industry; although the extent of the increase in trade is down to barriers to trade and geographical proximity. These manufacturing industries tend to be unionised which has in the past helped to drive up the relative wage in the industry. With the increase in imports, these benefits have been passed over to other countries, leaving workers to have to enter other jobs in often non-unionised sectors. This has only worsened the wage inequality by driving down wages for less-skilled workers. This combined with skill-biased technology change in many industries has rapidly increased wage inequality.

Former barriers to trade have been lowered as tariffs and charges could result in no trade. The existence of the present global market means that transportation costs are lower, transportation systems are more efficient and telecommunication systems have greatly improved. Developed countries have been shifted from the situation of a manufacturing autarky to a reliance on imports from developing countries and the production of skill intensive goods. This has lowered the demand for unskilled workers, leading to lower wage rates. Imports are highly labour intensive and displace many domestic workers. Unskilled labour in developing countries is very cheap; however it is also relatively cheap in developed countries compared with skilled labour.

Wood puts forward an interesting argument. He asks the question, if labour saving, cost saving technology exists, why are they not fully utilised in developed countries? Firms do not have complete knowledge of all technical possibilities and they have to incur research and development costs. It is better to import from countries who produce on a large scale and very cheaply.(18)

The graph highlights a strong negative correlation between the change in manufacturing employment share in a certain OECD country and the change in net imports of manufactures from developing countries (given as ratio of GDP). So, as manufacturing employment share decreases, the net imports from developing countries increase.

Reference, Pg 63:(18)

All the countries in the scatter plot shown above have increased their trade with developing countries. The horizontal axis shows the change across the period 1970-1990 in net imports of manufactures from developing countries measured as percentage share of GDP. The vertical axis shows the percentage point change in the share of manufacturing in total employment over the same period.

Countries with a higher increase in import penetration experienced a larger decrease in manufacturing employment, displaying an inverse relationship between them. There is a positive cross country correlation between changes in import penetration and unemployment rate. These results prove that trade has had an influence on production and employment levels in developed countries. It is interesting to note how a simple test shows strongly the effect of increasing trade with developing countries.

The fact that the horizontal axis numbers are small, is what economists who dismiss the trade effect draw upon. The largest rise in net import penetration was not much over two percent of GDP. So, how could such small numbers have such a profound effect?

To give us an idea, we can look at the 'factor content method'.

Factor Content of Trade

Wood provides a clear explanation and interpretation of the factor content of trade^(^19). The factor content of trade method highlights how trade has affected the labour market. This is important in the study of the effect of trade on wage inequality due to the link that exists between the labour market and wage inequality. Changes in supply or demand affect the wage level of the workers. When a certain type of worker is in high demand for example, they are of more value to an employee so this employee is willing to pay more for this worker. Trade is indirectly affecting wage inequality through the labour market, affecting the supply and demand of skilled and unskilled workers in different ways. The table of results uncovers some clear evidence as to how trade has affected the labour market and from this evidence, we can draw conclusions about wage inequality.

Trade liberalisation

In considering the effect of trade on wage inequality it is important to look at the free trade model as a relative comparison to what takes place in the real world. Within the workhorse model of liberalisation it is suggested that less educated workers in developing countries should benefit most from the opening up of world trade. This is due to patterns of trade bringing together the relative structure of wages and other factor prices across countries, and as such developing countries have the most to gain. However due to the change in market factor endowments post 1980's there has developed a wage inequality trend between the educated and less educated countries.

The purpose of trade liberalisation is to lower the costs involved in trade and to increase the countries level of exports. This in turn would lead to a relative increase in the price of labour due to the increase in demand, and this according to the classical theory would raise the total wage level of the industry .Goldberg and Pavcnik, (2004). Attanasio et al. (2004), identify three areas in which trade reform contributed to the increase in wage inequality: increasing returns to education, changes in industry premiums, and increases in the size of the informal sector (7). While there are others that argue that trade liberalisation has done nothing to increase wage inequality but that it has increased real wages for both skilled and unskilled labour. This is argued by Acemoglu (2003), who puts forward the idea that liberalisation has accelerated the increase in the technological progress, and it is this that explains the increase in real wages. (7)

"There is no doubt that trade can contribute to rising wage inequality. This does not, however, offer an argument for protection, or for turning our backs on openness. Rather, it makes a powerful case for attending to the social tensions arising from inequality, be this through public provision of basic services, better education and training opportunities or fiscal reform"

The WTO Director-General Pascal Lamy puts forward: (31)

The Stolper-Samuelson is used to help explain the differences in real wages brought about through protectionist policy. It asserts that an increase in the domestic price of a commodity, brought about due to the presence of a higher tariff or protectionist policy, will increase the real wages of labourers (6). This means that the real price of the commodity that is used relatively intensively during the course of production will increase. In this case we look at China producing textiles, which uses unskilled labour at a high intensity, and electronic goods, which uses highly skilled labour less intensively. If textiles were protected through policy the real wages of workers would increase, but not by as much as it would for the more skilled labourers in as selective labour market such as electronics, if they were to be protected instead.

Contrasting Views

| Contrasting Views |

|---|

| 1. Alternative Trade Theory i. Technnology ii. Education and Skill Premium iii. Other Explanations 2. Counter arguments to trade i. Development Patterns ii. Wealth Condensation |

Schools of Thought

| Economist/s | View |

|---|---|

| Trade | |

| Adrian Wood, 'How Trade Hurt Unskilled Workers' |

Argues for the 'minority' view amongst economists; that trade has had a profound effect on wage inequality in developed countries and is actually the main cause of the deteriorating situation for unskilled workers. |

| Bergstrand. Et al, 'The Changing Distribution of income in an Open U.S Economy' |

Increased imports of manufacturing durables is one of the main factors explaining sharp rise in U.S earnings inequality after 1979. |

| George Borjas and Valerie Ramey (1994) |

State flatly that "foreign competition in highly concentrated industries can account for much of the trend in wage inequality from 1963 to 1988". 4 (p.237). |

| Lynn Karoly and Jacob Klerman (1994) | Empirical data agrees with the views of Borjas and Ramey (1994). |

| John Bound and George Johnson (1993), Jeffrey Sachs and Howard Shatz (1994) |

Conclude that trade has played a small role in the trend toward increased earnings inequality. |

| Kevin M. Murphey and Finis welch (1991) and Borjas, Richard Freeman and katz (1992) | Find the evidence that the effect of trade on the earnings distribution was probable some what larger, especially between 1981 and 1986. |

| Deardorff and Hakura (1994) | State that it is just as reliable to describe international trade occurring as a result of wage differences as it is to say international trade affects wage changes within each country. |

| Technology | |

| Adrian Wood, 'How Trade Hurt Unskilled Workers' |

Although primarily focusing on trade leading to wage inequality, Wood considers how technological change has led to this increased trade therefore interlinking the two factors. |

| Adrian wood, 'North-South Trade, Employment and inequality' | Argues that growth of manufacturing exports from newly industrializing economies can explain not only the rise in earnings inequality throughout the industrialized world but also the trend towards higher joblessness in western Europe and north America. |

| Koster and Bhagwati,'Trade and Wages: Leveling Wages Down?' | International trade has played a minor role in lowering relative wages of unskilled labour. They argue that rising earnings inequality in the United States and other industrialized countries is mainly the result of technological change rather than pressure on unskilled workers' wages from foreign competition |

| Stephen Machin, 'Wage Inequality In The 1970s, 1980s and 1990s'' | Machin presents a technology based counter argument, statistcally attempting to show that international trade has had little bearing on wage inequlaity in the developed world, displaying the relationship between imports and skills upgrading. |

| Education (Skill-premiums) | |

| John Hassler, José V. Rodríguez Mora & Joseph Zeira (2007).'Inequality and mobility' | A main implication of the model is that differences in the amount of public subsidies to education and educational quality produce cross-country patterns with a negative correlation between inequality and mobility. Differences in the labour market, like differences in skill-biased technology or wage compression instead produce a positive correlation. |

| Cline, 1997; Winchester and Greenaway, (2006) |

The explanation for the rise in wage inequality in the US and the UK is that the skilled-to-unskilled wage ratio in both countries increased from 1.5 to 1.8 during the final decades of the twentieth century. |

References: (2, 4, 6, 8, 9, 18 )

Conclusion:

International trade can be seen to explain some of the changes in wage structure and to boost wage inequality, however there appears to be no single explanation to wage inequality. Immigration, education, minimum wages and skill-based technological change, as mentioned throughout, have all been proven to also contribute to wage inequality. Thus, it cannot be said that there is a single story in explaining the increase in wage inequality. International trade can go far in explaining the increasing wage gap between skilled and unskilled workers, however it fails to explain why wage inequality has increased within skill groups. A truly competent explanation of wage inequality will have to explain both the timing in the changes to wage inequality as well of the structure of these changes throughout the labour market as a whole.

Wage structure and inequality in developed countries has not evolved in the same way over the last two decades. The 90-10 wage gap comparison of 1984 vs.1994 shows that in Germany, wage inequality actually fell, despite the fact the country hugely boosted their international trade. Whilst, Japan, a pioneer in international trades wage inequality figures stayed static. This demonstrates how international trade, whilst accounting for elements of wage inequality can by no means explain it.

Paul Krugman began the recent presentation of his new study of trade and wages at the Brookings Institution. Krugman, a leading trade economist and also a New York Times columist concluded in his1995 Brookings paper that international trade with poor countries played only a small role in America's rising wage inequality. He states how international trade explains only 10% of the widening income gap between skilled and unskilled workers during the 1980s. Krugman has undertaken several studies throughout the 1990's and states that his findings have been the same. Krugman has been seen to have a very influential role in influencing ecomomists; based on his work it is now commonly accepted that trade was only a small player in causing wage inequality. ln line with the ricardian argument, Krugman claims that other factors, especially technological change are more liable for the change in wage inequality.

Harvard economist Robert Lawrence reaches very different conclusions. In a new book, "Blue Collar Blues", he claims that American inequality and international trade as the cause is flawed. He claims how the gap between white- and blue-collar workers has not risen that much since the late 1990s when China's global presence was made known. The wages of the least skilled has infact improved in comparison to those in the middle income bracket. He does however acknoweldge that some inequality has increased, he claims that there are noticeably large increases in the income of those at the highest end (the rich and super rich). However he claims there is nothing to suggest that wage inequality has reacted as expected by many economists or by traditional trade theory. Lawrence puts this down to the fact that America, has ceased to produce many low skilled, labour intensive goods, favouring to import them instead. As a result, there are no workers to lose out to foreign competition, as there simply is no competition. He further backs this claim up by stating that when there is competition, developed countries tend to favour machinery and only employ few skilled workers for their production methods. Thus, whilst competition from China may be seen to eliminate some jobs for skilled workers in developed countries, this does not affect wage inequality.

Stephen Machin opposes, his chapter, 'Wage Inequality In The 1970s,1980s and 1990s', argues that international trade has had little or no bearing on wage inequality in developed countries. His key points are as follows; firstly since the late 1970s wage inequality in Britain has risen faster than in most other developed nations to reach its highest levels this century and in the 1990s the pace of rising inequality slowed compard to the 1980s. Demand has been shifting in favour of the more highly educated and skilled, because despite the fact that there are many more workers with educational qualifications, their wages relative to other groups, have not fallen. Relative demand shifts in favour of the more educated and skilled are more pronounced in technologically advanced industires. This is in line with the notion that technology underlies much of the change in labour market inequality. Accordingly, there is much less evidence that increased international trade (measured in terms of observable indices of trade) has been strongly linked to rising labour market inequality. While Machin finishes with claiming, some of the rise in wage inequality can be attributed to the declining role of trade unions in the British labour market. (9)

Thus, there appears to be no single cause for wage inequality; although the globalisation of trade can be linked to it, there are many other notable factors. The Ricardian argument puts forward the idea of comparative advantage and therefore looks at areas such as technological advancement as the explanation of wage disparity. The Factor Proportion theory talks of scarcity and concentration of resources; the move away from labour intensive markets to those with a higher profit margin and an evolution of the skilled and unskilled labour market and thus wages. Theorists list a number of other causes of wage inequality; immigration, education, minimum wages, and skill-based technological change. International trade can explain to some extent the increase in the wage gap between the skilled and the unskilled, but not the rising inequality within skilled groups. Whilst it is not something we were asked to cover, discrimination in the form of gender and race discrimination can also be seen to play a huge part in wage inequality in the last 50 years as well as the increase of women in the labour market.

Therefore we may conclude that yes, increased international trade and globalisation does have an effect on wage inequality. However there is a real lack of finely tuned statistics, different measures can be seen to include different things and thus comparison is near-on impossible. Hence, given the current data, all we can conclude is that international trade is one of many influencers that has had an impact on wage inequality, but currently it is not possible to quantify it accurately.

References-

See separate Page for details.