| Tangentium |

January '05: Menu

All material on this site remains © the original authors: please see our submission guidelines for more information. If no author is shown material is © Drew Whitworth. For any reproduction beyond fair dealing, permission must be sought: e-mail drew@comp.leeds.ac.uk. ISSN number: 1746-4757 |

Permeable Portals: Designing congenial web sites for the e-societyRichard Coyne, John Lee and Martin ParkerPage 1 ¦ Page 2 ¦ Page 3 ¦ Page 4 ¦ Printer-friendly version ABSTRACT We examine the nature of the web portal and its design, starting from the assumption that there is a conflict between the freedoms suggested by the web and the apparent need for access restrictions felt most keenly by corporations and institutions. We draw on our own work and that of our students in designing web portals. Our investigation demonstrates the utility for design in pursuing the sociality of the gift, and the observation of the web site as fetish object. Our response to these issues of e-sociability is a designerly one, deploying design strategies as a way of exploring a problem domain. In this light encouraging and observing active usage over time emerges as a strategy for maintaining web security in low risk domains. 1. IntroductionCastells attributes the origins of the World Wide Web to the aspirations of the techno-elites, the meritocratic communities of scientists and researchers freely sharing expertise and information [1]. Advocates of hypertext see in the web an opportunity for non-linear, democratic, a-centric textual production, and the founders of the web see it as a medium of “mind to mind” communication [2]. The web is the main medium for purveying the ideals of open source, free software and freely distributed creative production [3]. The promotion and preservation of these freedoms of necessity requires legislation, standards, and vigilance, that sometimes conflict with the freedoms themselves. Who would want to contribute to an open source project if they thought that someone else might make propriety gain from their free labours, or exercise restrictive trade practices? The open access ethos is also prone to exploitation, in the form of invasive advertising, contamination by computer viruses, and digital espionage. In addition, as commercial and professional organisations use the web, they bring with them the culture of competition, the wish to preserve security, protect intellectual property, maintain corporate image, and protect from libel, misrepresentation and the charge of exclusivity. Whereas the ideals of the web as an open access medium may persist amongst home computer users and hackers, those easiest to sue (corporations and institutions) are likely to exercise the most restraint and present the most severe restrictions [4]. In these respects “web culture” simply presents a microcosm of public life, though it brings certain issues into relief in new ways, as evidenced in the recent controversy at the University of Birmingham when staff web sites hosted by the institution were apparently cut out of circulation after complaints about the content of one of the sites. The action prompted the creation of an off-site web page to elicit support for the restoration of academic freedoms. The use of the World Wide Web is caught between its supposed idealistic origins of open access, and its increasing institutionalisation and corporatisation. What is the character of the web portal within this problematic? From an institutional point of view, a web portal is simply a series of web pages, structured and organised to provide access to the information, facilities and services of an organization [5]. This “enterprise portal” may also provide relevant links to the rest of the web. It may have an Intranet component, with access restricted to members of the organisation or users within its domain. From the perspective of the web liberalist, the idea of the portal offers potential for access to communities, the exchange of ideas, experimentation, free speech and support for otherwise marginalised groups. From a more radical point of view the portal suggests the possibility of a chink in the borders around the restricted areas of corporate networked communications. For the antiestablishment revolutionary, the portal could be the hole in the corporate fence. The portal is one metaphor amongst many. Web pages are also receptacles, rooms, shops, plazas, a means of navigating across a sea of information, and hooks from which to string a network of associations. They offer a means of moulding the amorphous web into a particular image. Web pages are also incidental, symptoms of communicative practices (rather than receptacles) constituting traces, memories and palimpsests for socially constructed narratives. For idealistic e-communitarians there are no portals, just the ideal of free form access, perhaps best expressed in the ideals of hypertext [6]. But the designers of web sites, and designers who use the web, wrestle with the conflict between the open society and the corporate, the seamless and the fractured, the homogeneous and the richly textured and lumpy. In fact we can take our lead from the nature of the designed and built physical environment, which is already characterised by heterogeneity and discontinuity. We present the portal as a granular entity in an imperfect medium, through insights garnered from our own work in developing web portals with digital media design students. 2. Thresholds of resistanceWe operate within a design school in which the concept of boundaries and their permeability has particular currency [7] One of the major issues addressed in architecture is the permeability between inside and outside, the public versus the private, and the relationships between physical spaces. Architects also create entrances, doorways, passages, arches, prosceniums and portals, which are never just a gap for passage from the outside to the inside, but a place to linger, to retreat, to observe. In some climates thresholds to the outside are sharply defined and take up very little space. In temperate climates it is possible to make much of the threshold and provide a series of transitional spaces: porches, verandahs, alcoves, pergolas. Thresholds can be transition spaces. Spatial organisation involves the linking of thresholds as much as the manipulation of space (fig. 1). A building can be seen as a series of interlinked rooms, or a progression of threshold conditions. A threshold also suggests resistance. You have to cross over a step, open a door, negotiate a constriction, turn the key, swipe the card, hand over a ticket, bribe the gatekeeper, pass inspection. Thresholds also present in the urban landscape as the preferred sites of residency of the homeless, a propensity also in accord with various mythic accounts of journeying and dwelling [8].

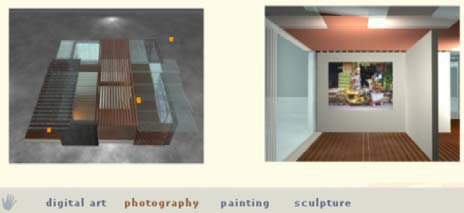

Figure 1. Three dimensional web portal design drawing on architectural metaphors, with inevitable reference to transition spaces and thresholds. The user enters a space in which artworks are arrayed, using Macromedia’s Shockwave 3D. Work by Manolis Minopoulos, Alex Thannhauser and Man Wang. We also deal in sound design and musical composition, which entail references to the threshold. Apart from the obvious threshold transition from performer to audience, there are sound parameters, such as amplitude or frequency, which can be gradually increased to a level beyond which some other condition sets in: a distortion effect, or in controlled circumstances the generation of another signal, or the propagation of a range of signals that trigger one another, as in the MAX/MSP multimedia programming environment for the creation of interactive art installations. The threshold trigger becomes a metaphor for the revolutionary impulse, where too much (amplitude, signal, information) produces a surge into a new condition (chaos, stasis, distortion, clarity). Contemporary music practice has also traded along the boundary condition, using music as the emblem for underground activity and putative subversion. Footnotes1. Castells, M. 1996. The Rise of the Network Society, Blackwell, Oxford. return 2. Landow, G.P., and Delany, P., 1994, Hypertext, Hypermedia and Literary Studies: The State of the Art. in Delany, P., and Landow, G.P., eds., Hypermedia and Literary Studies, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 3-50.: Tapia, A., 2003. Graphic Design in the Digital Era: The Rhetoric of Hypertext. In Design Issues, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 5-24.: Berners-Lee, T. 1999. Weaving the Web, London, Sage. return 3. Torvalds, L., and Diamond, D., 2000. Just for Fun: The Story of an Accidental Revolutionary. Texere, New York: www.gnu.org: creativecommons.org. return 4. Rezmierski, V.E., M.R., S.J., and N., S.C.I., 2002. University Systems Security Logging: Who Is Doing It and How Far Can They Go? In Computers and Security, Vol. 21, No. 6, pp. 557-564(8).: Sherwood, J., 1997. Security Issues in Today's Corporate Network. In Information Security Technical Report, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 8-17(10): Turega, M., 2000. Issues with Information Dissemination on Global Networks. In Information Management & Computer Security, Vol. 8, No. 5, pp. 244-248(5): Venter, H.S., 2000. Network Security: Important Issues. In Network Security, Vol. 2000, No. 6, pp. 12-16(5). return 5. Detlor, B., 2000. The Corporate Portal as Information Infrastructure: Towards a Framework for Portal Design. In International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 91-101(11). return 6. Landow and Delany, op. cit. return 7. Tschumi, B., 1994. Architecture and Disjunction. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. return 8. Hyde, L., 1998. Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth and Art. North Point Press, New York. return | |