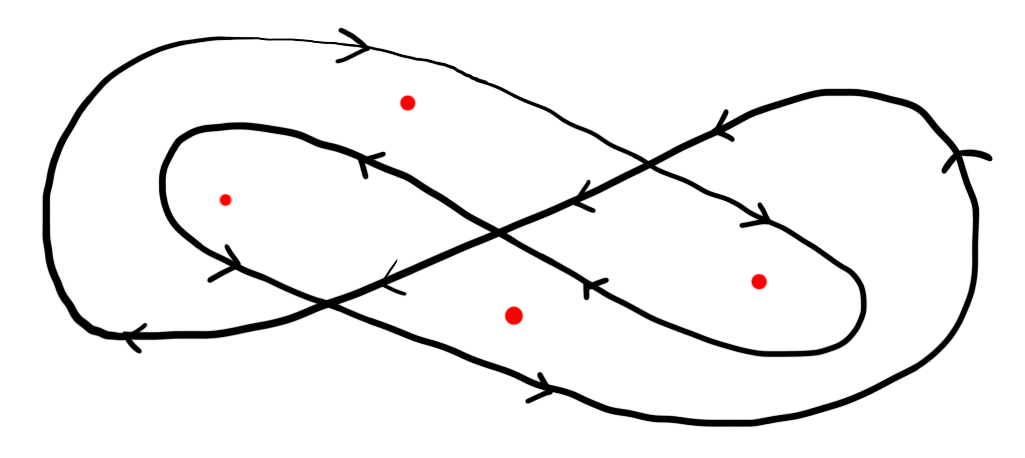

Figure 1: Which of the red points are inside the smooth path gamma?

Home | Assessment | Notes | Worksheets | Blackboard

It was crucial in our first version of Cauchy's theorem that the interior of the rectangle be entirely contained within $D$. This is because, in the proof, we have no control over the locations of the subrectangles $S(n)$ and the point $\zeta$ they are focusing in on but must be able to apply linearization at $\zeta$. We would like a more general version of Cauchy's theorem - we don't want to restrict ourselves to rectangles - but must then have some way of deciding whether the inside of our contour is entirely contained within our domain $D$. Deciding is not always simple!

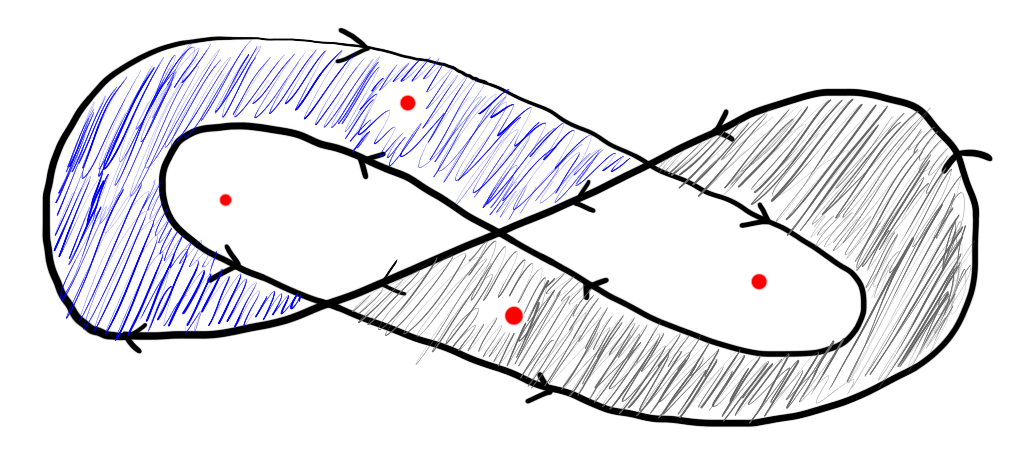

It is difficult to say at first glance which of the red points in the above image are inside the contour shown and which (if any) are not. However, after some thought it may become apparent that the path can be thought of as two contours, one winding around the left-most region and one winding around the right-most region. Thus we can think of two of the red points as being outside the path.

Figure 2: The path can be thought of a two contours, one winding around the blue region and one winding around the grey region.

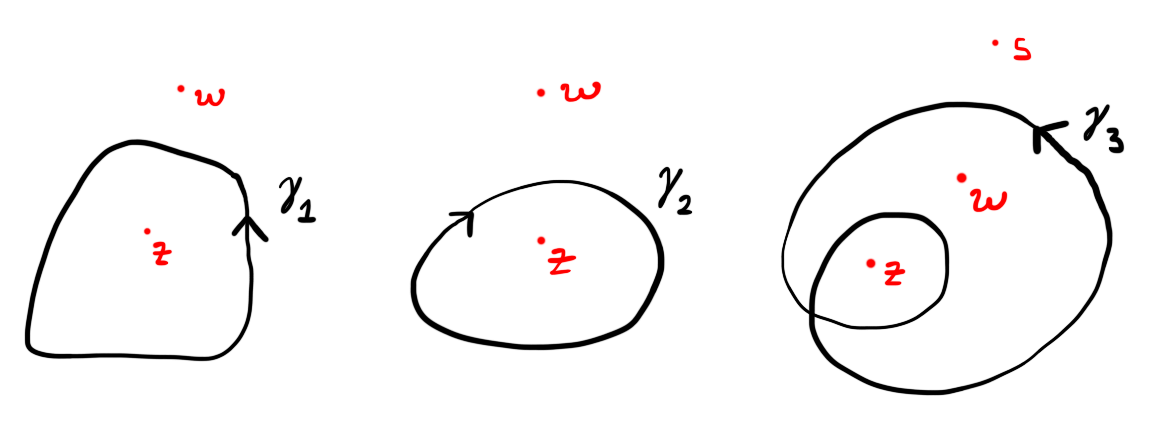

Our goal in this section is to come up with a formal description of whether a point is inside a closed contour or not. In fact we will do slightly more and come up with a formal description for how many times a closed contour winds around a point. Let $\gamma$ be a closed contour and let $z$ be a point that is not on $\gamma$. Imagine you have a piece of string. Tie one end to a pencil and place the tip of the pencil on the point $z$. Now trace around the closed path $\gamma$ with the other end of the piece of string. When you get back to where you started, the string will be wrapped around the pencil some number of times. This number (counted positively for anti-clockwise turns and negatively for clockwise turns) is the winding number of $\gamma$ around $z$ and is denoted $\wind(\gamma,z)$.

Figure 3: For $\gamma_1$ we have $\wind(\gamma_1,z) = 1$ and $\wind(\gamma_1,w) = 0$. For $\gamma_2$ we have $\wind(\gamma_2,z) = -1$ and $\wind(\gamma_2,w) = 0$. For $\gamma_3$ we have $\wind(\gamma_3,z) = 2$, $\wind(\gamma_3,w) = 1$ and $\wind(\gamma_1,s) = 0$.

In examples, it is often easy to calculate winding numbers by eye and this is how we shall always do it. However, in order to use winding numbers to develop the theory of integration, we shall need an analytic expression for the winding number $\wind(\gamma,z)$ of a closed path $\gamma$ around a point $z$. Let us first consider the case $z = 0$.

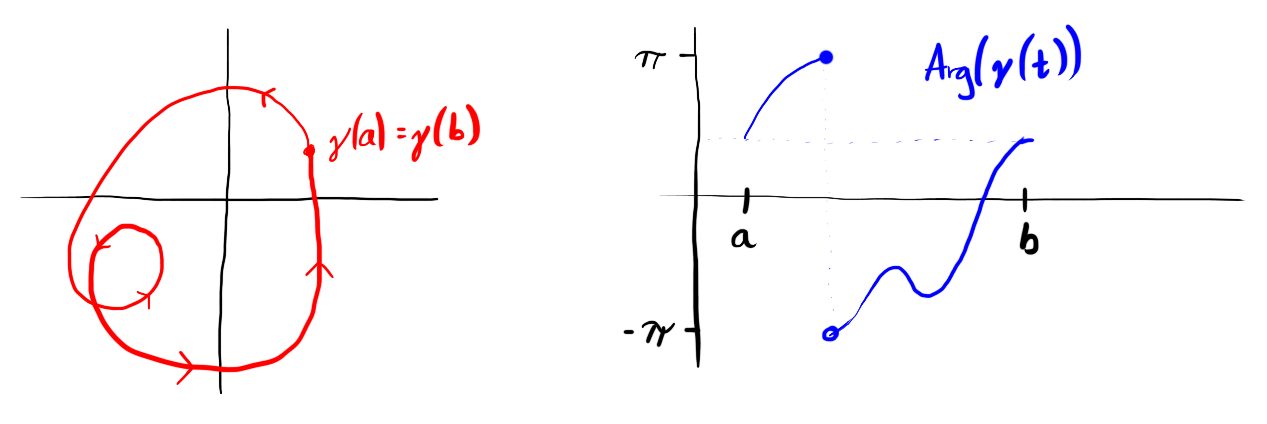

Fix a smooth path $\gamma : [a,b] \to \C \setminus \{0\}$. Lets look at $\Arg(\gamma(t))$ on $a \le t \le b$. As $t$ increases from $a$ to $b$ the argument of $\gamma(t)$ will vary. Sometimes it will jumo from $\pi$ to $-\pi$ and sometimes it will jump from $-\pi$ to $\pi$. These jumps correspont to windings of $\gamma$ anti-clockwise and clockwise around $0$ respectively.

Figure 4: The principal argument of $\gamma(t)$ has a jump from $\pi$ to $-\pi$ corresponding to wrapping once anti-clockwise around the origin.

Although counting jump discontinuities from the graph of $\Arg(\gamma(t))$ is straightforward, we will need to take a slightly different perspective to develop some theory.

Fix a path $\gamma : [a,b] \to \C \setminus \{0\}$. A function $\theta : [a,b] \to \R$ is a continuous argument for $\gamma$ if $\theta$ is continuous and $|\gamma(t)| e^{i \theta(t)} = \gamma(t)$ holds for all $a \le t \le b$.

The function $\theta(t) = \Arg(\gamma(t))$ will not usually be a continuous argument of $\gamma$. But if $\theta$ is a continuous argument of $\gamma$ then $\theta(t)$ is always an argument of $\gamma(t)$.

If $\theta$ is a continuous argument for the closed path $\gamma : [a,b] \to \C \setminus \{0\}$ then \[\wind(\gamma,0) = \frac{\theta(b) - \theta(a)}{2\pi}\] holds.

We will need the following theorem, which we will not prove.

Every path $\gamma : [a,b] \to \C \setminus \{0\}$ can be written in the form \[\gamma(t) = r(t) e^{i\theta(t)}\] where $r : [a,b] \to (0,\infty)$ is differentiable and $\theta : [a,b] \to \R$ is smooth and a continuous argument of $\gamma$.

We will finish this section with an analytic formula for the winding number.

Fix a smooth path $\gamma : [a,b] \to \C \setminus \{0\}$ that is closed. Then \[\wind(\gamma,0) = \frac{1}{2 \pi i} \int\limits_\gamma \frac{1}{z} \intd z\]

By the previous theorem we can write \[\gamma(t) = r(t) e^{i \theta(t)}\] with $r : [a,b] \to (0,\infty)$ differentiable and $\theta : [a,b] \to \R$ differentiable. Then \[\gamma'(t) = r'(t) e^{i \theta(t)} + r(t) i \theta'(t) e^{i \theta(t)}\] and \[\begin{aligned} & \int\limits_\gamma \frac{1}{z} \intd z \\ = & \int\limits_a^b \frac{r'(t) e^{i \theta(t)} + r(t) i \theta'(t) e^{i \theta(t)}}{r(t) e^{i \theta(t)}} \intd t \\ = & \int\limits_a^b \frac{r'(t)}{r(t)} \intd t + i \int\limits_a^b \theta'(t) \intd t \\ = & \ln( r(b) ) - \ln( r(a) ) + i \theta(b) - \theta(a) \vphantom{\int\limits_a^b} \\ = & 2 \pi i \wind(\gamma,0) \end{aligned}\] which is what we wanted to prove. $\square$

With the above theorem in hand, it is straightforward to prove via a substitution that \[\wind(\gamma,w) = \frac{1}{2\pi i} \int\limits_\gamma \frac{1}{z-w} \intd z\] for any smooth path $\gamma$ and any $w$ not on $\gamma$.

Recall that a contour is a family $\Gamma = (\gamma_1,\dots,\gamma_n)$ of smooth paths with each $\gamma_{i+1}$ starting where $\gamma_i$ ends. For a contour the winding number is defined to be \[\wind(\Gamma,z) = \wind(\gamma_1,z) + \cdots + \wind(\gamma_n,z)\] for any $z$ not on $\Gamma$.