|

| Further Reading: » For more information about this subject, the following resources are recommended. [1] MapQuest; Terraserver. [2] Eyeballing of Cryptome, April 2002. [3] See for example, "Vice president in secure location at night", by John King, CNN, 11th September 2002. [4] Eyeballing a Chem-Bio War Target, 25th April 2002. [5] See Eyeballing US Transatlantic Cable Landings, 7th July 2002; Eyeballing US Transpacific Cable Landings, 8th July 2002; Eyeballing Downtown Manhattan Telephone Hubs, 10th July 2002. [6] The homepage of Natsios

Young Architects. Young’s partner Deborah Natsios maintains

the Cartome website [7] For an interesting discussion of development and application of technologies of aerial photography, satellite imaging, GIS and like see Mark Monmonier's book Spying with Maps: Surveillance Technologies and the Future of Privacy (University of Chicago Press, 2002). [8] Many secret and many other more mundane facilities are hidden underground. There is growing interest in so called 'urban speleology,' exploring man-made underground structures; see for example the Subterranea Britannica website. For more in-depth coverage see for example Anthony Clayton's Subterranean City (Phillimore & Co Ltd, 2000) and Nick McCamley's Cold War Secret Nuclear Bunkers (Pen & Sword, 2002). [9] The Guardian newspaper did a short piece on a few secret sites in Britain in 2000, linked to a story on the availability of the first national aerial photography map, the 'millennium map', of the UK. "The Russians spent decades getting hold of pictures like these. Now anyone can order them on the net", by Felicity Lawrence and Richard Norton-Taylor, The Guardian, 27th January 2000. [10] This issue is clearly illustrated in the "UK secret site photos ‘must go", BBC News Online, 7th June 2002. More information on 'chilling' effect on access to public information by governments and private business, see the Chilling Effects Clearinghouse. [11] Mark Monmonier, How to Lie with Maps, 2nd edition (University of Chicago Press, 1996). [12] More information on the influential work of Brian Harley on the radical re-interpretation of cartography, see The New Nature of Maps: Essays in the History of Cartography, edited by Paul Laxton (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001). [13] For example see, Alexey V. Postnikov, "Maps for ordinary consumers versus maps for the military: double standards of map accuracy in Soviet cartography, 1917-1991", Cartography and Geographic Information Science, 2002, Vol. 29, No. 3, pages 243-260. [14] Website for the exhibition

and the accompanying book by April Carlucci and Peter Barber, Lie

of the Land: The Secret Life of Maps (The British Library,

2002).

|

| |

|

|||||||||||||||

| |

|

||||||||||||||

| |

Revealing Hidden Places: The Cryptome Eyeballing Map Series Maps can reveal hidden places that are beyond our sight. But they also have a unique power to deceive us by deliberately not revealing what is actually on the ground. Governments have many secret places, sensitive sites and critical infrastructures that they wish to remain hidden from prying eyes. The one government with the most to hide is undoubtedly the United States with its huge military and security apparatus, operating from innumerable bases and bunkers spread across the globe. Indeed, there is great fascination in contemporary culture - bordering on X-Files paranoiac obsession for some - with the activities of this military-industrial complex, and in particular with seeing what is behind the formidable fences and intimidating 'no entry' signs of its hidden places. The Eyeballing project <www.cryptome.org/eyeball.htm> developed by activist John Young uses publicly available maps to give a view into some of these secret and sensitive sites across America.

The project consists of series of individual 'eyeballing'

web pages, each of which focuses on a particular military base,

intelligence facility or other sensitive site, like nuclear power

plants and dams. Eyeballing exploits the potential of hypertext

to author a cartographic collage, piecing together a diverse range

of aerial photographs, topographic maps at different scales, photographs,

along with expert commentary by Young, annotated with corrections

and clarifications emailed in from (anonymous) readers. There are

also hyperlinks to supplementary documents and other relevant websites,

while individual eyeballs pages are themselves cross referenced

by hyperlinks. To produce the eyeballs Young only utilises public

sources of maps and imagery, typically topographic mapping from

MapQuest and aerial photography from Terraserver [1]. Even

though the 'eyeballs' have an unpolished, almost amateurish look

to them, the series represents a novel and valuable atlas of hidden

places.

Each eyeball spatialises a particular story of a hidden,

sensitive site, engaging with the reader to actively explore and

think what happens there. There are currently 172 individual

eyeballing web pages and the series continues to expand in numbers

and in its scope of subjects to map. So far the eyeballing series

has covered 11 airforce bases, 17 naval bases, the FBI, the CIA,

the National Security Agency (NSA), nerve gas storage facilities,

nuclear power plants, 54 dams, numerous little known intelligence

listening posts, as well as the Kennedy Space Centre, the Statue

of Liberty, and one particular family ranch in Crawford, Texas.

As well as the obvious sites, there are also some

unusual selections of eyeball targets that reveal the broad scope

of the project as well some of the idiosyncratic concerns of Young,

such as Las Vegas; He has even Eyeballed himself [2]. Much

of Young's interest is not with 'top secret' bunkers but with the

large number of facilities and infrastructures that are usually

obscured from public view and not really talked about. There is

still plenty more to do, of course, and he is working alone on the

project so it represents a considerable individual investment of

time and effort.

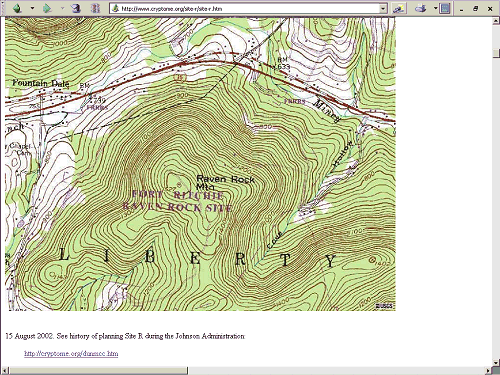

In a recent email interview, Map of the Month

asked John Young about the eyeballing project, focusing on his aims

and objectives in producing them. The project started in March 2002

as Young become intrigued by the continuing official ‘disappearance’

of the US Vice President Dick Cheney from post 9-11 Washington DC

to a secret bunker, which the media euphemistically reported as

a 'secure, undisclosed location' [3]. Young wanted "..to

locate the safe hole and publish it". The secure location

turned out to be a military command bunker, known as Site R, buried

under Raven Rock Mountain in rural Pennsylvania, close to Camp David.

This discovery provided the first eyeball

web page <http://cryptome.org/site-r.htm>,

a part of which is shown below.

Following on from the initial cartographic exposure of Site

R, Young eyeballed obvious, high profile, organisations like the

NSA, the FBI and the CIA, exposing their headquarters building complexes.

He also did a timely sequence looking at America's capacity

in terms of weapons of mass destruction in April 2002, eyeballing

probable storage of nerve gas [4]. The blurry and indistinct

views of these facilities in the remote deserts of Utah provide

a very pointed and potent reminder of the country in possession

of the most WMD. Young says that developing composites of multiple

sites, in order to expose "the extent of systems which cannot

be seen in a single facility has been a goal - as common among geographers."

The eyeballing of undersea cable systems and the telecommunications

hubs in New York City [5] are good examples of this.

Young is not a cartographer, instead he trained as an architect

and now runs a small practice in New York City with his partner

Deborah Natsios [6]. "As architects my wife and I

have long used maps and cartography in professional work",

according to Young, noting however, that this "has customarily

been quite local and limited compared to the eyeball series, and

none of our work has involved military facilities."

Young has a clear political agenda in creating the eyeballing

map montages, to show people the places that the powerful do not

want the rest of the community to know about or think about. The

mapping of facilities related to America’s continued maintenance

of weapons of mass destruction, for example, is clearly designed

to expose the hypocrisy of the Bush Government. Eyeballing is a

small and quite recent part of Young's activist work, dedicated

to exposing overbearing government and corporate secrecy, seeking

to reveal the murky workings of powerful organisations that wish

to operate hidden away from public scrutiny. He achieves this by

the unflinching disclosure of sensitive and controversial documents

via a unique information repository, an anti-secrecy library on

the Web, called Cryptome

<http://cryptome.org>, "which

has no limits and does not control its borrowed holdings",

says Young. The site has been online since 1996 and is an important

node in the realm of freedom of information, challenging powerful

interests particularly in the areas of surveillance technologies,

digital rights and cryptography. The Eyeballing project can be seen

as the subversive map room of the Cryptome library. Young has received

no official comment or complaint about the nature of his mapping

project thus far, but notes that eyeballing receives "quite

an impressive number of downloads from official websites, in particular

from the military".

"Maps are densely packed with information which helps

translate words into locations which may be visited either physically

or in the imagination" says Young. The Eyeballing pages

provide new vision that stimulates the imagination. They hint at

more than can actually be seen, making the viewer feel somehow illicit

in looking straight down onto some of the most secure and sensitive

places on the planet, such as the NSA headquarters. They give a

thrill at seeing something we are 'not meant to see' and yet the

maps themselves are entirely conventional, legal and publicly available.

This subversive feeling is created through the selection and then

unconventional arrangement of a specific set of maps. The matter-of-fact reality of the eyeball mapping actually helps to 'ground' some of these murky, anonymous and deliberately intimidating organisations. When we can see that they inhabit an ordinary office building, in a beltway sprawl of Washington DC for example, it begins to reel them into our everyday reality from the X-Files fringe, cartography dissolving their mystery. The eyeballs also give the audience a view that they could not normally get themselves, even if they wanted to. For most people it would be impossible to actually fly over the NSA complex in a plane.

The tactical exploitation of mapping in the eyeballing series

can also be read as placing the cartographic spotlight back onto

the powerful themselves, in a very small way of course. The best

mapping, in terms of accuracy and currency, has traditionally been

the exclusive preserve of the military, and the strategic advantages

this cartographic knowledge brings have been jealously guarded by

those in power. Indeed, much of the current mapping technologies

have military origins, most particularly for spying on enemies [7].

Yet, maps, even very detailed ones, can only tell us so much.

And Young himself is working within the constraints of freely available

public spatial data sources, which are often partial and out of

date. Consequently, the eyeballs he can produce only scratch the

surface of what is going on at these hidden and sensitive places.

We may snatch a glimpse of the buildings, roads and other visible

structures, but this is far from a panoptic view and grants the

reader little sense of the implications of what is being performed

daily at these sites. (Young's interpretative commentary does augment

the mapping to a significant amount.) The interconnections, flows

and chains of command, vital to the working of many hidden places,

cannot be observed in static maps of physical facilities. Aerial

photographs, topographic maps and satellite imagery can hint at

the nature of power, as materially expressed through the physical

structures, but they cannot actually show us power relationships.

Moreover, those organisations with something really worth

hiding have long been savvy to the watchful eyes above, putting

their most sensitive sites fully underground [8]. Maps showing

the access roads and entrance portals to such bunker complexes only

give the barest hint of their subterranean extent. Nowadays much

of the secret work of the military and intelligence community is

actually transacted in cyberspace, in the data networks, servers

and webs of classified information flows, which are again completely

invisible to conventional cartographic display of physical facilities.

Part of the wider of agenda of Young's Cryptome project is to try

to expose the actual workings of these virtual systems of security

and intelligence through publishing documentary evidence on their

structures, internal policies, statistics, budget details and other

banal, but revealing, administrative materials of the various organisations

involved.

Eyeballing has been made possible by the amount of detailed

spatial data, now publicly available on the Internet. These maps

are accessible and browsable to anyone online, through simple Web

interfaces. The fact that one does not require specialised knowledge

or software to use spatial data has greatly widened access. In recent

years a great deal of aerial photography and satellite imagery,

often from declassified military sources, as well as new commercial

satellite systems, has also become publicly available, although

the resolution and temporal scale of this imagery is still the poor

relation compared to what is produced by current classified military

systems. Clearly tensions may well arise between 'open skies' of

detailed commercially satellite imagery and the entrenched view

that the public should not know what is hidden behind walls and

fences.

Eyeballing demonstrates well the potential for novel applications

of spatial data, created by non-specialists, once it becomes easily

accessible, at least in an American context. It shows what can be

achieved in a quick, 'low-tech' fashion, by mixing and matching

publicly sourced maps and imagery. It would have been very much

harder to have created the eyeball web pages ten years ago for example,

particularly as a one-man effort.

However, it would certainly be a lot tougher to attempt

eyeballing outside the United States, as much of the rest of the

world is a long way behind the Americans in terms of access to detailed

spatial data freely available on the Internet, and quite often sensitive

sites, especially military facilities, are themselves censored from

published mapping. "It is frustrating to lack access to

eyeballing information outside the US like that available within",

commented Young, "the US centricity is distorting of what

information remains to be revealed about other countries."

There are hidden places and sensitive sites all over the world and

it would be interesting to see activists in other countries having

a go at mapping them [9]. "[W]e hope that the eyeball

series will induce other contributions of restricted and secret

mapping information from other countries as well as the US",

commented Young.

Yet, there are also worrying signs that the growth

in public availability of detailed spatial data may be coming to

a close. In the current ‘chilling’ atmosphere, of post

9-11 security paranoia, availability and easy access to whole rafts

of public information is being questioned. Spatial data, in particular,

can easily be portrayed as somehow especially 'sensitive' and of

likely value to terrorists [10]. The level of detail and

freedom of access to digital mapping and imagery enjoyed today,

may soon be locked away again, available only to 'authorised' users.

Young passionately says, "wider public access is under attack

by the secret keepers and should be fought vociferously".

All maps are distortions of reality, as they have

to be selective in what they show and do not show. Sometimes distortions

are imposed deliberately for overt purposes of propaganda or misinformation

and this works so well as people have an innate faith in maps as

truthful representations of reality. Mark Mommonier's book How

to Lie With Maps [11] nicely debunks the myth of cartographic

objectivity.

So

clearly, John Young's work in the eyeballs series only gives a pinhole

view into the world of hidden places, but it is a revealing view

nonetheless, and being freely distributed through the Web, it could

be argued that the eyeballs are potent maps of resistance to the

growing secret state, turning the tools of the watchers onto themselves.

Map of the Month asked Young about his 'dream' eyeballing

map, without current practical restrictions, and this is what he

said: "This would map surveillance systems of the world

and methods of hiding those by artfully camouflaging with public

disinformation."

|

||||||||||||||

| |

© 2003 Martin Dodge, Cyber-Geography Research |

||||||||||||||