This is a printer-friendly version of this feature essay. Return to this month's introduction.

ABSTRACT

We examine the nature of the web portal and its design, starting from the assumption that there is a conflict between the freedoms suggested by the web and the apparent need for access restrictions felt most keenly by corporations and institutions. We draw on our own work and that of our students in designing web portals. Our investigation demonstrates the utility for design in pursuing the sociality of the gift, and the observation of the web site as fetish object. Our response to these issues of e-sociability is a designerly one, deploying design strategies as a way of exploring a problem domain. In this light encouraging and observing active usage over time emerges as a strategy for maintaining web security in low risk domains.

Castells attributes the origins of the World Wide Web to the aspirations of the techno-elites, the meritocratic communities of scientists and researchers freely sharing expertise and information [1]. Advocates of hypertext see in the web an opportunity for non-linear, democratic, a-centric textual production, and the founders of the web see it as a medium of “mind to mind” communication [2]. The web is the main medium for purveying the ideals of open source, free software and freely distributed creative production [3]. The promotion and preservation of these freedoms of necessity requires legislation, standards, and vigilance, that sometimes conflict with the freedoms themselves. Who would want to contribute to an open source project if they thought that someone else might make propriety gain from their free labours, or exercise restrictive trade practices?

The open access ethos is also prone to exploitation, in the form of invasive advertising, contamination by computer viruses, and digital espionage. In addition, as commercial and professional organisations use the web, they bring with them the culture of competition, the wish to preserve security, protect intellectual property, maintain corporate image, and protect from libel, misrepresentation and the charge of exclusivity. Whereas the ideals of the web as an open access medium may persist amongst home computer users and hackers, those easiest to sue (corporations and institutions) are likely to exercise the most restraint and present the most severe restrictions [4].

In these respects “web culture” simply presents a microcosm of public life, though it brings certain issues into relief in new ways, as evidenced in the recent controversy at the University of Birmingham when staff web sites hosted by the institution were apparently cut out of circulation after complaints about the content of one of the sites. The action prompted the creation of an off-site web page to elicit support for the restoration of academic freedoms. The use of the World Wide Web is caught between its supposed idealistic origins of open access, and its increasing institutionalisation and corporatisation.

What is the character of the web portal within this problematic? From an institutional point of view, a web portal is simply a series of web pages, structured and organised to provide access to the information, facilities and services of an organization [5]. This “enterprise portal” may also provide relevant links to the rest of the web. It may have an Intranet component, with access restricted to members of the organisation or users within its domain. From the perspective of the web liberalist, the idea of the portal offers potential for access to communities, the exchange of ideas, experimentation, free speech and support for otherwise marginalised groups. From a more radical point of view the portal suggests the possibility of a chink in the borders around the restricted areas of corporate networked communications. For the antiestablishment revolutionary, the portal could be the hole in the corporate fence.

The portal is one metaphor amongst many. Web pages are also receptacles, rooms, shops, plazas, a means of navigating across a sea of information, and hooks from which to string a network of associations. They offer a means of moulding the amorphous web into a particular image. Web pages are also incidental, symptoms of communicative practices (rather than receptacles) constituting traces, memories and palimpsests for socially constructed narratives. For idealistic e-communitarians there are no portals, just the ideal of free form access, perhaps best expressed in the ideals of hypertext [6]. But the designers of web sites, and designers who use the web, wrestle with the conflict between the open society and the corporate, the seamless and the fractured, the homogeneous and the richly textured and lumpy. In fact we can take our lead from the nature of the designed and built physical environment, which is already characterised by heterogeneity and discontinuity. We present the portal as a granular entity in an imperfect medium, through insights garnered from our own work in developing web portals with digital media design students.

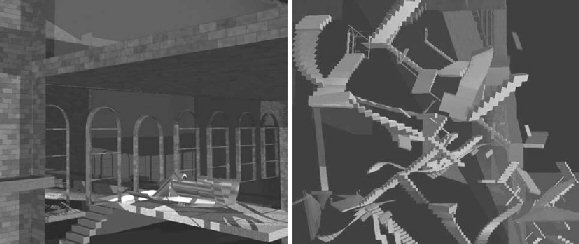

We operate within a design school in which the concept of boundaries and their permeability has particular currency [7]. One of the major issues addressed in architecture is the permeability between inside and outside, the public versus the private, and the relationships between physical spaces. Architects also create entrances, doorways, passages, arches, prosceniums and portals, which are never just a gap for passage from the outside to the inside, but a place to linger, to retreat, to observe. In some climates thresholds to the outside are sharply defined and take up very little space. In temperate climates it is possible to make much of the threshold and provide a series of transitional spaces: porches, verandahs, alcoves, pergolas. Thresholds can be transition spaces. Spatial organisation involves the linking of thresholds as much as the manipulation of space (fig. 1). A building can be seen as a series of interlinked rooms, or a progression of threshold conditions. A threshold also suggests resistance. You have to cross over a step, open a door, negotiate a constriction, turn the key, swipe the card, hand over a ticket, bribe the gatekeeper, pass inspection. Thresholds also present in the urban landscape as the preferred sites of residency of the homeless, a propensity also in accord with various mythic accounts of journeying and dwelling [8].

Figure 1. Three dimensional web portal design drawing on architectural metaphors, with inevitable reference to transition spaces and thresholds. The user enters a space in which artworks are arrayed, using Macromedia’s Shockwave 3D. Work by Manolis Minopoulos, Alex Thannhauser and Man Wang.

We also deal in sound design and musical composition, which entail references to the threshold. Apart from the obvious threshold transition from performer to audience, there are sound parameters, such as amplitude or frequency, which can be gradually increased to a level beyond which some other condition sets in: a distortion effect, or in controlled circumstances the generation of another signal, or the propagation of a range of signals that trigger one another, as in the MAX/MSP multimedia programming environment for the creation of interactive art installations. The threshold trigger becomes a metaphor for the revolutionary impulse, where too much (amplitude, signal, information) produces a surge into a new condition (chaos, stasis, distortion, clarity). Contemporary music practice has also traded along the boundary condition, using music as the emblem for underground activity and putative subversion.

In human-computer interface design, people talk of the mouse click as offering resistance. Some think that in a good web design you should be no more than 3 clicks from the information you seek. The mouse click presents a binary threshold condition. You cannot linger on a click as you can in a doorway. Perhaps the hyperlinked text string or button is the threshold, a place of anticipation. As for a closed door, there is some promise, an opportunity to assess risk: will the click open a new window or a new frame? Will it clutter the screen? Will I be able to hit the return button to get back? The page is a space, but perhaps it is just a threshold. The information is the target, and the page is just a means of getting access to it. By this reading all that the web presents is thresholds. The web page is the shop counter, the ticket box, the interface, and the space beyond is the butter in the fridge, being in Paris, the bouquet of flowers in a vase. The first or front page in a hierarchically structured web site is also a major point of admission and resistance. Sometimes it is a shop front, a billboard, a welcome mat, that encourages or impedes progress. The most conspicuous portal device is that of the login and password, where progress is impeded further by the necessity to register, invent a name, think of a password, fill in a form, disclose personal details, sometimes without knowing what uses will be made of them (fig. 2).

Fig. 2: The password as conspicuous threshold

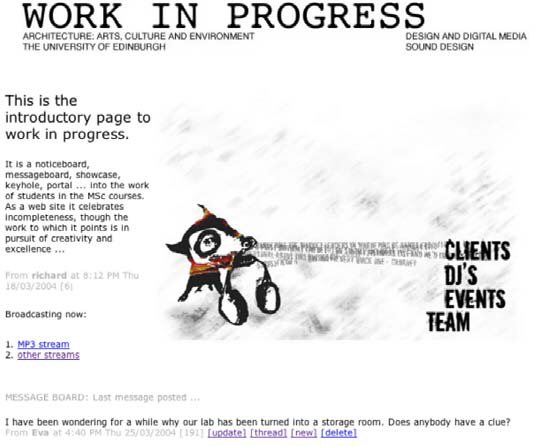

The boast is that this ritual provides access to a community. Once you are a member you have free access to its resources. This is a very impermeable threshold, providing very little in the way of glimpses to what is inside, or a place to linger. WebCT technologies provide such portals for student access to learning resources. But it is sometimes highly desirable for prospective clients (students) to gain access to lectures (in whole or in part), student work and internal communications. We have developed our own simple permeable portal, which provides access to work in progress, message boards, and a newsletter (fig. 3). It entails risks, in that anyone from outside can intrude on the message boards and place and delete messages. After operating this site for eight months, we have not found any invasion from the outside. As an active site it will be interesting to see what means of regulation emerge if this happens. At the moment we are too cautious to provide unlimited access to all lecture notes, so we have password protection. Outsiders can see parts of certain documents but need to email us for the password to see the texts in their entirety.

Fig. 3: Work-in-progress site, with images and messages generated by the user community. Image by Colin Calnan.

Our students have also experimented with strategies for permeable access to potentially sensitive material, such as their own designs, databases of online registrants, imagined product lines, and communications within the group. Database applications such as ColdFusion provide high level control of web information in database formats. Data can be inserted into and retrieved from a database and is displayed as HTML web pages by the ColdFusion server, complete with interactive components, forms and images. Though online databases are rigorously formal entities with firewalls to control access, they also provide a simple means of establishing communication that has few restrictions. For example, the content of a form on a web page filled in by anyone on the web can then be displayed as database content on a web page. We use this as the basis of our message board that is accessible to anyone with a web browser.

So far we have presented a simple exercise in the idea of permeability across a digital threshold. The literary theorist, Lewis Hyde has related the issue of threshold directly to commerce [9]. Ancient cities were characterised by various gateways and levels of permeability. The inner reaches of the city, perhaps in the sanctity of the domestic sphere or the temple precinct, were characterised by certain freedoms, a generous sociability. At the gate of the city control is more vigorous, driven by the imperative to exclude invaders. Commerce, trade and the harsh rule of law take place at the gate of the city. The inner sanctum, the hearth, the altar is the preserve of the gift.

The sociality of the web has been described as participation in the culture of the gift. There is the celebrated case of the development of the Linux operating system by teams of programmers working voluntarily and without payment, often in isolation [10]. Open source software participates directly in this culture. In terms of the metaphor of the city it extends the city to global dimensions. The gate of the city is pushed further and further from the hearth, or perhaps the hearth assumes global dimensions.

But even in the realm of Internet commerce the gift can be in evidence. Traces of the gift are ubiquitous in commerce [11]. A site that gives nothing away, that does not participate at least in part in the gift culture of the Internet is unlikely to win the trust of consumers. The question for web design is not just “what are you selling?” but “what does your site give away?” — information, service, the pleasure of browsing, directness, instantaneity, anonymity? Our students explored the gifts of free information, news, images and interactive maps in their project work. The imperative was to create a web site that would also entail the potential for an income stream, which involves the tantalizing game of giving in order to elicit interest and possibly a sale. But even the processes of buying and selling can participate in the trappings of the gift, as we think of the incorporation of the financial transaction in a kind of game, or adding the gift of an extra service to the purchase, such as organizing transportation to a performance venue on purchase of a ticket (or vice versa) (fig 4).

The web already purports to offer a rich cornucopia of information and opportunities, as a gift. To mix a metaphor, the web is also suggestive of a rich flow that we can tap into, or a seam to be mined.

Fig. 4: A site that offers the gift of a transportation service. Work by Allan Henderson, Francesca Matera and Mitra Abrahams.

The portal suggests an opening through which people, objects, or information may be transacted. The ideas of temporality and flow are also promoted by the medium of sound (as a time-based medium). Since the introduction of smooth packet switching protocols and improved bandwidth, it is common to think of the web as a broadcast medium. The portal becomes a transmitter. Or perhaps there is a stream or channel flowing past into which we can tap. The URL link provides a portal into this flow. The sound medium readily promotes a culture of evasion, abetted by the fact that a sound source is often difficult to detect. We have created streams of sound on our work-in-progress website, and students are experimenting with the continuous transmission of video and sound, and with timed broadcast events.

This idea of flow feeds back into the production of graphical web sites as we think of sites that change in a time-based way. One simple device is to maintain a database of images created by students from which a random selection is made each time you load the web page. The page can change its form and appearance, perhaps thereby straining the relationship between form and content. The information delivered determines to some extent the appearance of the site (fig 3), and this varies over time. This is an intriguing concept that is still being explored.

What of the temporality of the portal? Doors are sometimes left ajar, fully opened, closed tight or locked, and this depends on the time of day and the activities around the door. The web portal can similarly exhibit a time dimension, responding to cycles and activities. During vacation periods access could be restricted in some way. When there is a lot of activity then anyone can have free access and post messages, as then the community is minding its domain. We will return to this possibility subsequently.

The random presentation of text and imagers is suggestive of the idea of collage, where meanings emerge by virtue of unusual juxtapositions [12]. This happens as we arrange web pages from different sites on a computer screen. A page from a bookseller is juxtaposed against an online ticketing system, in turn juxtaposed with a word processor page, and with a broadcast radio channel playing in the background. With broadband communications it is possible for an author (or designer) to array all of these resources, as distractions, or as a multitude of concurrent portals from which new insights emerge by virtue of their imaginative combination. By various accounts this juxtaposition is in the nature of the workings of metaphor [13].

We have suggested that the portal is a metaphor. It is also a metonym. Technically a metonym is a subspecies of metaphor in which a part stands in for some whole. To use a picture of a knife and fork to represent a restaurant, or to depict a house with an icon of a front door would be metonymic. User interfaces are replete with metonymic references. Desmet relates this to concepts of the web as fetish [14]. A fetish is an application of metonymy, particularly in the case of altars and shrines constructed in certain cultures. The devout assembly of a hair brush, handkerchief, theatre ticket, lock of hair, or bracelet serves as a reminder of someone, or some occasion, and such objects may be arranged on a wall, table or cabinet. The arrangement is improvisational, personal, and has the character of a bricolage, presenting strange juxtapositions, that in turn suggest new meanings. The whole is an attempt to grapple with some situation that transcends the mere monetary or use value of the parts (love, loss, adoration, fortune, reverence).

Desmet constructs an interesting argument about the tensional relationship between metonymy and the more transcendent character of metaphor. We do not need to explore this further here, suffice it to say that the arrangement of the fetish objects acts as a portal to some supposedly transcendent condition. There are strong resonances with the character of web pages here. Arguably, the prototypical web page is not the well designed, controlled, corporate e-commerce site, but the humble personal web page: the instinctual, improvisatory page made up of favourite colour schemes, fonts, personal details, pictures of pets, and links, easily dismissed as risky, amateur self indulgence. To what transient entity does the page refer: freedom, self expression, participation in a community, asserting one’s place in the world? The web is a unique medium for circulating this fetishistic propensity, and for transforming and taming it. By this account the display of database content, the online collection, or the corporate web portal is a diminished extension of a more primitive and domestic mode of expression, which belongs at the hearth of the city.

A fetish is also an obsession. A shoe fetishist may have rooms full of trainers. To fetishise is to reduce something to metonymic status, as when an architect makes a fetish of the idea of the column and parades them to extreme effect (as at the Czernin Palace in Prague). Rather than ennoble the idea of the column it can diminish it, or render it ludicrous (or “mannerist” in architectural terms). This overindulgence is one of Marx’s complaints about the fetish of consumption [15]. Mass production and mass consumption reduce everything to the commodity. Unlike the fetish of the devotee, here the fetish is a trivialisation. The sociality of e-consumption is answerable to this charge.

One can also make a fetish out of security. It is easy enough to reduce issues of access to matters of how best to exclude and contain. This would be tantamount to architects using bank vaults and prisons as their models of access. Security in portal design is no less subtle. Our argument is that the permeable portal requires more design finesse than is suggested by the supposed imperative of network security.

But what if we have a multiplicity, an over-indulgence, a surfeit, of portals? As we have already hinted, the web can be thought not only as a series of spaces into which one gains access via a special site or link, but as a surfeit of interconnected links. This is not just to give priority to links rather than nodes, but to acknowledge the place of the web as a matrix of entrances and exits, a profusion of links, with the content of a page as an ever-receding and transient moment in the relentless quest for information. Here we would have something of the evasive character of text as perpetrated in the rhetoric of hypertextuality, and something akin to the elusive concept of the rhizome, as promoted by Deleuze and Guattari [16]. Were we to translate this surfeit back to the architectural metaphor of spaces and doors then we might end up with an architecture such as that depicted in fig. 5, or the cute but clever fetishisation of doors in the animated film Monsters Inc.

But portals do not exist in isolation. Unlike the city gate, many digital channels can be open at once, some streaming content, others offering potential, some affording glimpses, others gaping wide. It is the multiplicity of portals and their various conditions that provides the value of networked computing, as we integrate, synthesis, compare, and juxtapose. These are common processes for designers, who are used to drawing stimulation from a promiscuous range of sources. Now the Internet provides this profusion, which is not without dangers. But who, as an author, can resist the temptation to use a Web search engine as an instant means of checking up on a “fact,” the usage of a word, or conjure up an appropriate image? Then, when these images a thrown together we have a “portal” into something new. Permeability and profusion enable this to happen.

Fig. 5. Portal fetish: a series of portals in navigable three-dimensional space. Images by Armeet Panesar.

We have presented a polemic on the idea of permeability. Permeability is risky, but rendered feasible simply by the fact that a site is actively in use. In the risk society [17], leaving the door of your house open to the street is hazardous, but less so if there is a stream of active comings and goings, and if trusted neighbours are passing by. Crowds are not always safe places, but active communities where people are watching out for each other are as secure as it can get. Architecture and urbanism have long been suspicious of fortress design, where higher fences and more CCTV cameras are meant to reduce antisocial behaviour. The result is barren cityscapes made up of impermeable walls, uninhabitable edges, and devoid of people and activity. Where they succeed in barring delinquency at all, they also exclude carers and concerned citizens.

In the case of our work-in-progress site, security is maintained due to its constant use by a community. A stranger would be challenged, which is not to say un-welcomed. But what about the holiday periods, when the site is barely in use, or if the site simply peters out into disuse and we forget to check it. This is when security is most likely to be an issue. This is the downtown office precinct on a Sunday, or the holiday camp out of season. There is a temporal dimension. The next phase is to configure our work-in-progress web site so that it exhibits successive degrees of permeability depending on use. So if there is a period when the site is hardly in use then the gate swings shut, and you need the password to reopen it. As long as messages are being posted, and there is friendly traffic, then the restrictions diminish: your password cookie has a longer life, or you don’t require a password at all. This is an automated solution to a low risk problem, but one that could be extended to other corporate and institutional contexts, as one strategy to encourage permeable portals.

Thanks are due to Bruce Currey for drawing the matter of inclusion and permeability to our attention.

1. Castells, M. 1996. The Rise of the Network Society, Blackwell, Oxford.

2. Landow, G.P., and Delany, P., 1994, Hypertext, Hypermedia and Literary Studies: The State of the Art. in Delany, P., and Landow, G.P., eds., Hypermedia and Literary Studies, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 3-50.: Tapia, A., 2003. Graphic Design in the Digital Era: The Rhetoric of Hypertext. In Design Issues, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 5-24.: Berners-Lee, T. 1999. Weaving the Web, London, Sage.

3. Torvalds, L., and Diamond, D., 2000. Just for Fun: The Story of an Accidental Revolutionary. Texere, New York: www.gnu.org: creativecommons.org.

4. Rezmierski, V.E., M.R., S.J., and N., S.C.I., 2002. University Systems Security Logging: Who Is Doing It and How Far Can They Go? In Computers and Security, Vol. 21, No. 6, pp. 557-564(8).: Sherwood, J., 1997. Security Issues in Today's Corporate Network. In Information Security Technical Report, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 8-17(10): Turega, M., 2000. Issues with Information Dissemination on Global Networks. In Information Management & Computer Security, Vol. 8, No. 5, pp. 244-248(5): Venter, H.S., 2000. Network Security: Important Issues. In Network Security, Vol. 2000, No. 6, pp. 12-16(5).

5. Detlor, B., 2000. The Corporate Portal as Information Infrastructure: Towards a Framework for Portal Design. In International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 91-101(11).

6. Landow and Delany, op. cit.

7. Tschumi, B., 1994. Architecture and Disjunction. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

8. Hyde, L., 1998. Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth and Art. North Point Press, New York.

9. Hyde, L., 1983. Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property. Random House, New York.: Hyde 1998, op. cit.

10. Torvalds and Diamond, op. cit.

11. Godbout, J.T., 1998. The World of the Gift. McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal.

12. Coyne, R., 1999. Technoromanticism : Digital Narrative, Holism, and the Romance of the Real. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

13. Coyne, R., 1995. Designing Information Technology in the Postmodern Age : From Method to Metaphor. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.: Turbayne, C.M., 1970. The Myth of Metaphor. University of South Carolina Press, Columbia.

14. Desmet, C., 2001. Reading the Web as Fetish. In Computers and Composition, Vol. 18, pp. 55-72.

15. Marx, K., 1977, Capital. in McLellan, D., ed., Karl Marx: Selected Writings Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 415- 507.

16. Bolter, J.D., 2001. Writing Space : Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, N.J.: Tapia, op. cit: Deleuze, G., and Guattari, F., 1988. A Thousand Plateaus : Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Athlone Press, London: Smith, R.G., 2003. World City Actor-Networks. In Progress in Human Geography, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 25-44.

17. Beck, U., 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Sage, London.